Textus Receptus

From Textus Receptus

(→Editio Regia) |

Current revision (13:09, 8 December 2024) (view source) (→English translations of the Textus Receptus) |

||

| (146 intermediate revisions not shown.) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | [[Image:Holbein-erasmus.jpg|200px|thumb|right|[[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] did not "invent" the [[Textus Receptus]], but | + | [[Image:Holbein-erasmus.jpg|200px|thumb|right|[[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] did not "invent" the [[Textus Receptus]], but merely printed a small collection of what was already the vast majority of [[New Testament]] Manuscripts. The first printed Greek [[New Testament]] was the [[Complutensian Polyglot Bible|Complutensian Polyglot]] ([[1514 AD|1514]]) but was not published until eight years later, [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]' was the second Greek [[New Testament]] printed and published in ([[1516 AD|1516]]).]] |

| - | '''Textus Receptus''' ([[Latin]]: "received text") is the name subsequently given to the succession of printed [[Greek language|Greek]] texts of the [[New Testament]] which constituted the translation base for the original [[German]] [[Luther Bible]], for the translation of the [[New Testament]] into [[English]] by [[William Tyndale]], the [[King James Version]], and for most other Reformation-era [[New Testament]] translations throughout Western and [[Central Europe]]. The series | + | '''Textus Receptus''' ([[Latin]]: "[[received text]]") is the name subsequently given to the succession of printed [[Greek language|Greek]] texts of the [[New Testament]] which constituted the translation base for the original [[German]] [[Luther Bible]], for the translation of the [[New Testament]] into [[English]] by [[William Tyndale]], the [[King James Version]], and for most other [[Reformation]]-era [[New Testament]] translations throughout [[Western Europe|Western]] and [[Central Europe]]. The series flowed from both the [[Byzantine_text-type|Byzantine]] and [[Latin]] traditional texts, and the first printed [[Greek New Testament]] was the [[Complutensian Polyglot]] in [[1514 AD|1514]] which was not published until eight years later. The second Greek New Testament printed and published in [[1516 AD|1516]] called the [[Novum Instrumentum omne|Greek New Testament]]; a work undertaken in [[Basel]] by the [[Netherlands|Dutch]] scholar and Christian humanist [[Desiderius Erasmus]]. Erasmus did not "invent" the Textus Receptus, but merely printed a small collection of what was already the vast majority of New Testament Manuscripts. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] had devoted at least 15 years to the initial project, studying and collecting [[biblical manuscript|manuscripts]] from all over Europe. He had collated many [[Greek]] [[New Testament]] manuscripts and was surrounded by several language translations and also a multitude of verses from the commentaries and writings of [[Origen]], [[Cyprian]], [[Ambrose]], [[Basil of Caesarea|Basil]], [[John Chrysostom|Chrysostom]], [[Cyril]], [[Jerome]], and [[Augustine]]. [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] had access to [[Codex Vaticanus]] and [[Codex Bezae]], but rejected most of the readings of [[Codex Vaticanus|Vaticanus]] as corrupt, as did the [[King James Translators]]. The text [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] chose had an outstanding history in the [[Greek]], [[Syrian]] and [[Waldensian]] churches. [[Robert Estienne]] and [[Theodore Beza]] continued [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]' work and it became the standard Greek New Testament text. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Pre-16th Century== | ||

| + | Textus Receptus type manuscripts and versions have existed as the majority of texts for almost 2000 years. [[Frederick von Nolan]] spent 28 years tracing the Textus Receptus to apostolic origins. [[John William Burgon]] supported his arguments with the opinion that the [[Codex Alexandrinus]] and [[Codex Ephraemi]], were older than the [[Sinaiticus]] and [[Vaticanus]]; and also that the [[Peshitta#Syriac_New_Testament|Peshitta]] translation into [[Syriac]] (which supports the Byzantine Text), originated in the 2nd century around [[150 AD|150 A.D.]]. [[Papyrus 66]] used the Textus Receptus. The [[157 AD|157 A.D.]] Italic Church in the Northern Italy used the Textus Receptus. The [[177 AD|177 A.D.]] Gallic Church of Southern France used the Textus Receptus. The Celtic Church used the Textus Receptus. The Waldensians used the Textus Receptus. The Gothic Version of the 4th or 5th century used the Textus Receptus. The Curetonian Syriac is basically the Textus Receptus. Vetus Itala is from Textus Receptus. [[Codex Washingtonianus]] of Matthew used the Textus Receptus. [[Codex Alexandrinus]] in the Gospels used the Textus Receptus. 99% of extant [[New Testament]] manuscripts all used the Textus Receptus. The [[Greek Orthodox Church]] used the Textus Receptus. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Greek manuscript evidences point to a Byzantine/Textus Receptus majority. 85% of papyri used Textus Receptus, only 13 represent text of Westcott and Hort. 97% of uncial manuscripts used Textus Receptus, only 9 manuscripts used text of Westcott and Hort. 99% of minuscule manuscripts used Textus Receptus, only 23 used text WH. 100% of lectionaries used the Textus Receptus. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Received Text== | ||

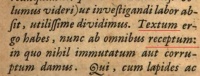

| + | [[Image:1633 Textus Receptus quote.JPG|200px|thumb|right|''textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum, in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus'' - from the [[1633 AD|1633]] Greek New Testament produced by [[Abraham Elzevir]] and his nephew [[Bonaventure Elzevir|Bonaventure]] who were printers at Leiden]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The origin of the term "Textus Receptus" comes from the publisher's preface to the [[1633 AD|1633]] edition produced by [[Abraham Elzevir]] and his nephew [[Bonaventure Elzevir|Bonaventure]] who were printers at Leiden: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :''Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum: in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus.'' Translated "so you hold the text, now received by all, in which nothing corrupt." | ||

| + | |||

| + | The two words, ''textum'' and ''receptum'', were modified from the [[accusative]] to the [[nominative]] case to render ''textus receptus''. Over time, this term has been retroactively applied to [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]' editions, as his work served as the basis of the others. The term "Textus Receptus" has also been used to refer to the early church fathers quotes containing "Textus Receptus" type readings, and it is also used as a synonym for Byzantine type texts, the [[Majority Text]], and any reading that is supportive of the Textus Receptus used to underlie the [[King James Version]]. Unlike the editions of Erasmus, Estienne (Stephanus), and Beza before them, the Elzevirs were not editors of the editions attributed to them, only the printers. The [[1633 AD|1633]] edition was edited by [[Jeremias Hoelzlin]], Professor of [[Greek]] at Leiden. | ||

| + | |||

| + | William Fulke (1538-1589) used the term "received text" in his book ''Defense of the Sincere and True Translations'' (Fulke's 49th response), to describe the Latin and also the commonly accepted texts in certain ages. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Verses about receiving the words of God''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Matthew 13: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :19 When any one heareth '''<u>the word</u>''' of the kingdom, and understandeth ''it'' not, then cometh the wicked ''one'', and catcheth away that which was sown in his heart. This is he which '''<u>received seed</u>''' by the way side. | ||

| + | :20 But he that '''<u>received the seed</u>''' into stony places, the same is he that heareth '''<u>the word</u>''', and anon with joy '''<u>receiveth it</u>'''; | ||

| + | :21 Yet hath he not root in himself, but dureth for a while: for when tribulation or persecution ariseth because of the word, by and by he is offended. | ||

| + | :22 He also that '''<u>received seed</u>''' among the thorns is he that heareth '''<u>the word</u>'''; and the care of this world, and the deceitfulness of riches, choke '''<u>the word</u>''', and he becometh unfruitful. | ||

| + | :23 But he that '''<u>received seed</u>''' into the good ground is he that heareth '''<u>the word</u>''', and understandeth ''it''; which also beareth fruit, and bringeth forth, some an hundredfold, some sixty, some thirty. | ||

| + | |||

| + | John 10:18: | ||

| + | :No man taketh it from me, but I lay it down of myself. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again. '''<u>This commandment</u>''' have '''<u>I received</u>''' of my Father. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Acts 2:41: | ||

| + | :Then they that '''<u>gladly received his word</u>''' were baptized: and the same day there were added ''unto them'' about three thousand souls. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Acts 7:38: | ||

| + | :This is he, that was in the church in the wilderness with the angel which spake to him in the mount Sina, and ''with'' our fathers: '''<u>who received the lively oracles to give unto us</u>''': | ||

| + | |||

| + | Acts 7:53: | ||

| + | :'''<u>Who have received the law by the disposition of angels</u>''', and have not kept ''it''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Acts 8:14: | ||

| + | :Now when the apostles which were at Jerusalem heard that Samaria had '''<u>received the word of God</u>''', they sent unto them Peter and John: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Acts 11:1: | ||

| + | :And the apostles and brethren that were in Judaea heard that the Gentiles had also '''<u>received the word of God</u>'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Acts 17:11: | ||

| + | :These were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they '''<u>received the word</u>''' with all readiness of mind, and '''<u>searched the scripture</u>'''s daily, whether those things were so. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1 Corinthians 15:3: | ||

| + | :For '''<u>I delivered unto you</u>''' first of all '''<u>that which I also received</u>''', how that Christ died for our sins '''<u>according to the scriptures</u>'''; | ||

| + | |||

| + | Galatians 1:9: | ||

| + | :As we said before, so say I now again, If any ''man'' preach '''<u>any other gospel</u>''' unto you than that '''<u>ye have received</u>''', let him be accursed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1 Thessalonians 1:6: | ||

| + | :And ye became followers of us, and of the Lord, '''<u>having received the word</u>''' in much affliction, with joy of the Holy Ghost: | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1 Thessalonians 2:13: | ||

| + | :For this cause also thank we God without ceasing, because, '''<u>when ye received the word of God which ye heard of us, ye received ''it'' not ''as'' the word of men, but as it is in truth, the word of God</u>''', which effectually worketh also in you that believe. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hebrews 7:11: | ||

| + | :If therefore perfection were by the Levitical priesthood, (for under it the '''<u>people received the law</u>''',) what further need ''was there'' that another priest should rise after the order of Melchisedec, and not be called after the order of Aaron? | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2 Peter 1:17: | ||

| + | :For '''<u>he received from God the Father</u>''' honour and glory, '''<u>when there came such a voice</u>''' to him from the excellent glory, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2 John 1:4: | ||

| + | :I rejoiced greatly that I found of thy children walking in truth, as '''<u>we have received a commandment from the Father</u>'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Revelation 3:3: | ||

| + | :'''<u>Remember therefore how thou hast received and heard</u>''', and hold fast, and repent. If therefore thou shalt not watch, I will come on thee as a thief, and thou shalt not know what hour I will come upon thee. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == History of the Printed Textus Receptus == | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Complutensian Polyglot==== | ||

| + | ''See Also [[Complutensian Polyglot]]'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Complutensian Polyglot]] is the name given to the first printed polyglot of the entire Bible, initiated and financed by [[Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros]]. It contained the first printed [[Greek New Testament]]. Although the [[New Testament]] was printed in [[1514 AD|1514]] its release was delayed until the [[Old Testament]] was completed in [[1517 AD|1517]]. By this time [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] had printed his [[Novum Instrumentum omne]] and obtained an exclusive four-year publishing privilege from Emperor Maximilian and Pope Leo X in [[1516 AD|1516]]. Because of [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]' exclusive privilege, publication of the Polyglot was delayed until Pope Leo X could sanction it in [[1520 AD|1520]]. It is believed to have not been distributed widely before [[1522 AD|1522]]. It included the first printed editions of the [[Greek New Testament]], the complete Septuagint, and the [[Targum Onkelos]]. It came as a six-volume set. The first four volumes contains the [[Old Testament]]. Each page consists of three parallel columns of text: Hebrew on the outside, the [[Latin Vulgate]] in the middle, and the Greek [[Septuagint]] on the inside. On each page of the [[Pentateuch]], the Aramaic text (the [[Targum Onkelos]]) and its own Latin translation are added at the bottom. The fifth volume, the [[New Testament]], consists of parallel columns of Greek and the [[Latin Vulgate]]. The sixth volume contains various [[Hebrew]], [[Aramaic]], and [[Greek]] dictionaries and study aids. The [[Complutensian Polyglot]] remains as a strong witness against those textual critics who claim Erasmus "invented" the Textus Receptus as most of the readings are akin to [[Erasmus]]' editions of the [[Greek New Testament]]. | ||

| - | |||

====Novum Instrumentum omne==== | ====Novum Instrumentum omne==== | ||

| + | [[Image:ErasmusText LastPage Rev22 8 21.jpg|thumb|180px|right|The last page of the Erasmian New Testament ([[Revelation 22:8|Rev 22:8]]-[[Revelation 22:21|21]])]] | ||

''See Also [[Novum Instrumentum omne]]'' | ''See Also [[Novum Instrumentum omne]]'' | ||

| - | [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] had been working for years on two projects: a collation of [[Greek]] texts and a fresh [[Latin]] [[New Testament]]. In [[1512 AD|1512]], he began his work on a fresh [[Latin]] [[New Testament]]. He collected all the [[Vulgate]] manuscripts he could find to create a critical edition. Then he polished the [[Latin]]. He declared, "''It is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better [[Latin]].''" Erasmus was keen to amend the old Vulgate and poured his life into the project: "''My mind is so excited at the thought of emending Jerome’s text, with notes, that I seem to myself inspired by some god. I have already almost finished emending him by collating a large number of ancient manuscripts, and this I am doing at enormous personal expense''." | + | [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] had been working for years on two projects: a collation of [[Greek]] texts and a fresh [[Latin]] [[New Testament]]. In [[1512 AD|1512]], he began his work on a fresh [[Latin]] [[New Testament]]. He collected all the [[Vulgate]] manuscripts he could find to create a critical edition. Then he polished the [[Latin]]. He declared, "''It is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better [[Latin]].''" [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] was keen to amend the old Vulgate and poured his life into the project: "''My mind is so excited at the thought of emending Jerome’s text, with notes, that I seem to myself inspired by some god. I have already almost finished emending him by collating a large number of ancient manuscripts, and this I am doing at enormous personal expense''." |

While his intentions for publishing a fresh [[Latin]] translation are clear, it is less clear why he included the [[Greek]] text. Though some speculate that he intended on producing a critical [[Greek]] text or that he wanted to beat the [[Complutensian Polyglot Bible|Complutensian Polyglot]] into print, there is no evidence to support this. Rather his motivation seems to be simpler: he included the [[Greek]] text to prove the superiority of his [[Latin]] version. He wrote, | While his intentions for publishing a fresh [[Latin]] translation are clear, it is less clear why he included the [[Greek]] text. Though some speculate that he intended on producing a critical [[Greek]] text or that he wanted to beat the [[Complutensian Polyglot Bible|Complutensian Polyglot]] into print, there is no evidence to support this. Rather his motivation seems to be simpler: he included the [[Greek]] text to prove the superiority of his [[Latin]] version. He wrote, | ||

| Line 17: | Line 97: | ||

:"''But one thing the facts cry out, and it can be clear, as they say, even to a blind man, that often through the translator’s clumsiness or inattention the [[Greek]] has been wrongly rendered; often the true and genuine reading has been corrupted by ignorant scribes, which we see happen every day, or altered by scribes who are half-taught and half-asleep.''" | :"''But one thing the facts cry out, and it can be clear, as they say, even to a blind man, that often through the translator’s clumsiness or inattention the [[Greek]] has been wrongly rendered; often the true and genuine reading has been corrupted by ignorant scribes, which we see happen every day, or altered by scribes who are half-taught and half-asleep.''" | ||

| - | Erasmus's new work was published by [[Johann Froben|Froben]] of [[Basel]] in [[1516 AD|1516]] and thence became the first ''published'' [[Greek New Testament]], the ''[[Novum Instrumentum omne]], diligenter ab Erasmo Rot. Recognitum et Emendatum''. Erasmus was surrounded with Bible manuscripts from his childhood in the 1460s, until the publication of his Greek Text in 1516. This is over 40 years! He worked for a dozen years on the text itself. | + | [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]'s new work was published by [[Johann Froben|Froben]] of [[Basel]] in [[1516 AD|1516]] and thence became the first ''published'' [[Greek New Testament]], the ''[[Novum Instrumentum omne]], diligenter ab Erasmo Rot. Recognitum et Emendatum''. The first Greek edition included Erasmus’ edited Latin text. [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] was surrounded with Bible manuscripts from his childhood in the 1460s, until the publication of his Greek Text in 1516. This is over 40 years! He worked for a dozen years on the text itself. “''The preparation had taken years''” (Durant, p. 283). |

| - | He used manuscripts: [[Minuscule 1|1]], [[Minuscule 2814|1<sup>rK</sup>]], [[Minuscule 2|2<sup>e</sup>]], [[Minuscule 2815|2<sup>ap</sup>]], [[Minuscule 2816|4<sup>ap</sup>]], [[Minuscule 7|7]], | + | He used manuscripts: [[Minuscule 1|1]], [[Minuscule 2814|1<sup>rK</sup>]], [[Minuscule 2|2<sup>e</sup>]], [[Minuscule 2815|2<sup>ap</sup>]], [[Minuscule 2816|4<sup>ap</sup>]], [[Minuscule 7|7]], [[Minuscule 817|817]]. |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | Scrivener wrote: | |

| + | :the colophon at the end of Erasmus' first edition, a large folio of 1,027 pages in all, is dated February, 1516 ; the end of the Annotations, March 1, 1516 ; Erasmus' dedication to Leo X, Feb. 1, 1516 ; and Froben's Preface, full of joyful hope and honest pride in the friendship of the first of living authors, Feb. 24, 1516. [https://archive.org/details/cu31924092355118/page/n193/mode/1up] | ||

| - | The overwhelming success of [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]' [[Greek New Testament]] completely overshadowed the [[Latin]] text upon which he had focused. Many other publishers produced their own versions of the [[Greek New Testament]] over the next several centuries. | + | ====Novum Testamentum omne==== |

| + | |||

| + | ''See Also [[Novum Testamentum omne]]'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The second edition used the more familiar term ''Testamentum'' instead of ''Instrumentum,'' and eventually became a major source for [[Martin Luther|Luther]]'s [[German language|German]] translation. In second edition ([[1519 AD|1519]]) [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] acquired also [[Minuscule 3]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With the third edition of [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]' [[Greek]] text ([[1522 AD|1522]]) the [[Comma Johanneum]] was included, because a single 16th-century Greek manuscript ([[Minuscule 61|Codex Montfortianus]]) had subsequently been found to contain it, though [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] had expressed doubt as to the authenticity of the passage in his ''Annotations''. Popular demand for [[Greek New Testament]]s led to many authorized and unauthorized editions in the early sixteenth century; almost all of which were based on [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]'s work and incorporated his particular readings, although typically also making a number of minor changes of their own. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The overwhelming success of [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]]' [[Greek New Testament]] completely overshadowed the [[Latin]] text upon which he had focused. Many other publishers produced their own versions of the [[Greek New Testament]] over the next several centuries. The first separate printing of the Greek text in any format was in 1521 which follows the improved 1519 Erasmus text. Even while Erasmus was still at work on his Greek NT and Latin re-translation, Nicholas Gerbelius, the editor of the edition at hand, wrote to him on 11 September 1515 to urge that the Greek should be printed separately for convenience (Tregelles, Account, p. 20). It has been suggested that it was this 1521 separate edition that Martin Luther actually worked from in translating his “September” New Testament of 1522. (Reuss, p. 30 and Darlow and Moule note at 4598) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Sessa==== | ||

| + | In [[1538 AD|1538]] Ioannes Antonius de Sabio printed a Greek New Testament edition which was funded by Melchior Sessa. | ||

====Editio Regia==== | ====Editio Regia==== | ||

''See Also [[Editio Regia]]'' | ''See Also [[Editio Regia]]'' | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

[[Image:NT Estienne 1551.jpg|thumb|right|180px|4th edition of New Testament of Robert Estienne]] | [[Image:NT Estienne 1551.jpg|thumb|right|180px|4th edition of New Testament of Robert Estienne]] | ||

| + | [[Robert Estienne]], known as Stephanus ([[1503 AD|1503]]-[[1559 AD|1559]]), a printer from Paris, edited four times the [[Greek New Testament]], [[1546 AD|1546]], [[1549 AD|1549]], [[1550 AD|1550]], and [[1551 AD|1551]], the last in [[Geneva]]. The first two are among the neatest Greek texts known, and are called ''O mirificam''; the third edition is a splendid masterpiece of typographical skill. It has critical apparatus in which quoted manuscripts referred to the text. Manuscripts were marked by symbols (from α to ις). He used ''Polyglotta Complutensis'' (symbolized by α) and 15 [[Greek]] manuscripts. In this number manuscripts: [[Codex Bezae]], [[Codex Regius (New Testament)|Codex Regius]], minuscules [[Minuscule 4|4]], [[Minuscule 5|5]], [[Minuscule 6|6]], [[Minuscule 2817|2817]], [[Minuscule 8|8]], [[Minuscule 9|9]]. The third edition is known as the [[Editio Regia]]; the edition of [[1551 AD|1551]] contains the [[Latin]] translation of [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] and the [[Vulgate]], is exceedingly rare. It was in this edition that the division of the [[New Testament]] into verses was for the first time introduced. | ||

| - | + | ====Beza==== | |

| - | The | + | See Also ''[[Theodore Beza]]'' |

| + | |||

| + | The third edition of [[Robert Estienne|Estienne]] (Stephanus) was used by as the basis of the Greek New Testament editions of [[Theodore Beza]] ([[1519 AD|1519]]-[[1605 AD|1605]]), who edited it nine times between [[1565 AD|1565]] and [[1604 AD|1604]]. In the critical apparatus of the second edition he used the [[Codex Claromontanus]] and the [[Syriac]] [[New Testament]] published by [[Emmanuel Tremellius]] in [[1569 AD|1569]]. [[Codex Bezae]] was twice referenced (as [[Codex Bezae]] and β' of [[Robert Estienne|Estienne]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;The introduction to the 1582 New Testament: | ||

| + | :CHRISTIANO LECTORI THEODORUS | ||

| + | |||

| + | :Beza Gratiam et pacem a Domino. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :Quid sit a nobis, Christiane lector, ope Dei Opt. Max. fretis in hac tertia hujus voluminis editione praestitum, sic paucis cognosce. Hos Novi Foederis libros non modo cum variis septemdecim Gr aecorum codicum a Roberto Stephano, beatae memoriae viro, citatorum lectionibus rursum contulimus, sed etiam cum Syra interpretatione, ut est a doctissimo Emanuele Tremellio edita, et seorsim quoque Actorum Apostolicorum historiam et utranque ad Corinthios epistolam cum Latina ex Arabico sermone versione fratris ac symmystae nobis observandi Francisci Junii sedulo comparavimus. Multa quo- que in priore quidem horum librorum parte, id est in quatuor Evangelistis et Actis Apos- tolicis ex manuscripto Graecolatino ex D. Irenaei coenobio Lugdunensi eruto, et majus- culis utrinque literis descripto, tantaeque vetustatis codice ut ipsius pene Irenaei temporibus extitisse videri possit, nisi ex Graecia fuisse ante aliquot secula importatum ex aliis indiciis constaret. In posteriore vero, id est Pauli epistolis, ex alio paris vetusta- tis exemplari in Claromontano apud Bellovacos coenobio reperto" plurima non parvi momenti observavimus. Denique in Latina ipsius contextus interpretatione nostra paucula quaedam facere meliora studuimus, in annotationibus quaedam partim ab amicis admo- niti, partim judicio nostro emendavimus, quaedam sustulimus, multa prius non animad- versa suis locis adjecimus. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :Tu vero, Christiane lector, feliciter his nostris laboribus utinam tibi tam utilibus quam illos sumus magnos ac diuturnos experti feliciter fruere, et si quid ex iis fructus collegeris, Deo mecum gratias age, ad ca vero dijudicanda in quibus caecutivisse me existimaveris, eum, quaeso, candorem adfer qui Christiano conveniat et synceritati ac diligentiae in his observandis meae respondeat. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :Bene vale. Genevae, XX Februarii, anno ultimi temporis MD LXXXII. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Translated as: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :CHRISTIAN LECTOR THEODORE | ||

| + | |||

| + | :Grace and peace from the Lord. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :What is to be done by us, Christian reader, by the help of God Opt. Max. Relying on the third edition of this volume, let us know a few things. We have added these books of the New Testament not only with the various readings of the seventeen Greek codices quoted by Robert Stephanus, a man of blessed memory, but also with the Syriac interpretation, as published by the learned Emanuele Tremellio, and separately also the history of the Acts of the Apostles and the two epistles to the Corinthians with the Latin from the Arabic language we carefully prepared the version of the brother and symmyst Francis Junius to observe for us. Many things indeed in the former part of these books, that is, in the four Gospels and Acts of the Apostles, from a Greek manuscript excavated from the convent of D. Irenaeus in Lyons, and written in large letters on both sides, and a code of such antiquity that it seems to have existed almost in the time of Irenaeus himself unless it is clear from other evidence that it was imported from Greece several centuries ago. In the latter, that is, of Paul's epistles, from another copy of the same antiquity found in the monastery of Claromontano at Bellovaco, we observed many things of no small importance. based on it, we have partly corrected it by our own judgment, we have taken up some things, and we have added many things which had not been noticed before to their places. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :But you, Christian reader, may these labors of ours be as useful to you as those of our great and long experience, and if you reap any fruits from them, give thanks to God with me. , bring forth a whiteness that is worthy of a Christian and responds to my sincerity and diligence in observing these things. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :Good bye. Geneva, the 20th of February, in the last year of the year 82 MD. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====The Underlying Text of the King James Version==== | ||

| + | See Also ''[[King James Version]]'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The English [[King James Version]] of 1611 primarily used the 1598 of Beza, but departs from it in about 20 translatable places. [[Edward Hills]] wrote: | ||

| + | :"the King James Version ought to be regarded not merely as a translation of the Textus Receptus but also as an independent variety of the Textus Receptus." | ||

| + | |||

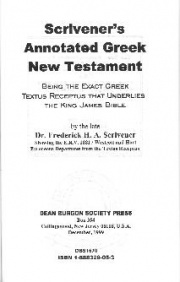

| + | In [[1881 AD|1881]] [[Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener]], attempted to recreate the text underlying the KJV. It was based upon the [[1598 AD|1598]] of Beza, but departs in 190 places (see [[191 Variations in Scrivener’s 1881 Greek New Testament from Beza's 1598 Textus Receptus]]), following at times, earlier readings of [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] and [[Robert Estienne|Stephanus]], and sometimes following the printing errors of the original [[1611 AD|1611]] [[Authorized Version]]. As mentioned, the 190 number is too high and it departs from it in about 20 translatable places. | ||

| + | |||

| + | From a scholarly perspective, following the unprinted Greek underlying the KJV is a reasonable position, due to the scholarship of the translators, and also the close adherence to the 1598 of Beza. But modern text critics have caused confusion by the demonization of the "King James Only" movement. While some cultic and spurious characters who hold to King James Onlyism have been highlighted, many reject this position because of ''guilt by association'' and choose a Textus Receptus position. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Elzevir Family==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Elzevir's published three editions of the Greek New Testament. The dates being; [[1624 AD|1624]], [[1633 AD|1633]] and [[1641 AD|1641]]. The Elzevir text is practically a reprint of the text of Beza 1565 with about fifty minor differences in all. The Elzevirs were notable printers, and their editions of the Greek New Testament were accurate and elegant. They were of Flemish ancestry and were famous printers for several generations. Throughout Europe the Elzevir editions came to occupy a place of honor, and their text was employed as the standard one for commentary and collation. The text of this 1633 edition became known as the "Textus Receptus" because of an advertisement in [[Daniël Heinsius|Heinsius']] preface that said in Latin ''Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum: in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus'', 'Therefore you have the text now received by all in which we give nothing altered or corrupt.' The Elzevir editions are collated against Estienne 1550 in the appendix of Tregelles 1854, and in Newberry 1877, Scrivener 1861, and Hoskier 1890. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Scrivener==== | ||

| + | The Greek New Testament which is sold by the [[Trinitarian Bible Society]] today, was edited by [[Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener]] | ||

| + | is the same as the text of [[Theodore Beza|Beza]]'s [[1598 AD|1598]] fourth edition, except for [[191 Variations in Scrivener’s 1881 Greek New Testament from Beza's 1598 Textus Receptus|191 places]], in which [[Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener|Scrivener]] amended his text using earlier editions of the Textus Receptus. | ||

== Textual criticism and the Textus Receptus == | == Textual criticism and the Textus Receptus == | ||

| + | [[Kurt Aland]] said in 1987: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“Finally it is undisputed that from the 16th to the 18th century orthodoxy’s doctrine of verbal inspiration assumed this Textus Receptus. It was the only Greek text they knew, and they regarded it as the original text.” ~ Kurt Aland (Trinity Journal, Fall 1987) | ||

[[John Mill]] ([[1645 AD|1645]]-[[1707 AD|1707]]), collated textual variants from 82 Greek manuscripts. In his ''Novum Testamentum Graecum, cum lectionibus variantibus MSS'' (Oxford [[1707 AD|1707]]) he reprinted the unchanged text of the ''Editio Regia'', but in the index he enumerated 30,000 textual variants. | [[John Mill]] ([[1645 AD|1645]]-[[1707 AD|1707]]), collated textual variants from 82 Greek manuscripts. In his ''Novum Testamentum Graecum, cum lectionibus variantibus MSS'' (Oxford [[1707 AD|1707]]) he reprinted the unchanged text of the ''Editio Regia'', but in the index he enumerated 30,000 textual variants. | ||

| - | Shortly after Mill published his edition, [[Daniel Whitby]] ([[1638 AD|1638]]-[[1725 AD|1725]]), | + | Shortly after Mill published his edition, [[Daniel Whitby]] ([[1638 AD|1638]]-[[1725 AD|1725]]), critiqued his work. He claimed that the autographs of the [[New Testament]] were identical to the Textus Receptus, and that the text had never been corrupted. He believed the text of the Holy Scripture was endangered by the 30,000 variants in Mill's edition. Whitby claimed that every part of the [[New Testament]] should be defended against these variants. |

[[Johann Albrecht Bengel]] (1687-1752), in 1725 edited ''Prodromus Novi Testamenti Graeci Rectè Cautèque Adornandi'', in 1734 edited ''Novum Testamentum Graecum''. Bengel divided manuscripts into families and subfamilies. He favoured (''[[lectio difficilior potior]]''). | [[Johann Albrecht Bengel]] (1687-1752), in 1725 edited ''Prodromus Novi Testamenti Graeci Rectè Cautèque Adornandi'', in 1734 edited ''Novum Testamentum Graecum''. Bengel divided manuscripts into families and subfamilies. He favoured (''[[lectio difficilior potior]]''). | ||

| Line 46: | Line 182: | ||

[[Johann Jakob Wettstein]]. His Apparatus was fuller than of any previous editor. He introduced the practice of indicating the [[List of New Testament uncials|ancient manuscripts]] by capital Roman letters and the [[List of New Testament minuscules|later manuscripts]] by Arabic numerals. He published in Basel ''Prolegomena ad Novi Testamenti Graeci'' (1731). | [[Johann Jakob Wettstein]]. His Apparatus was fuller than of any previous editor. He introduced the practice of indicating the [[List of New Testament uncials|ancient manuscripts]] by capital Roman letters and the [[List of New Testament minuscules|later manuscripts]] by Arabic numerals. He published in Basel ''Prolegomena ad Novi Testamenti Graeci'' (1731). | ||

| - | [[Johann Jakob Griesbach|J. J. Griesbach]] (1745-1812) combined the principles of Bengel and Wettstein. He enlarged the Apparatus by | + | [[Johann Jakob Griesbach|J. J. Griesbach]] (1745-1812) combined the principles of Bengel and Wettstein. He enlarged the Apparatus by more [[List of New Testament Church Fathers|citations from the Fathers]], and various versions, such as the Gothic, the Armenian, and the Philoxenian. Griesbach distinguished a Western, an Alexandrian, and a Byzantine Recension. [[Christian Frederick Matthaei]] (1744-1811) was a Griesbach opponent. |

| - | [[Karl Lachmann]] (1793-1851), was the first who broke with the Textus Receptus. His object was to restore the text to the form in which it had been read in the ancient Church about A.D. 380 | + | [[Karl Lachmann]] (1793-1851), was the first who broke with the Textus Receptus. His object was to restore the text to the form in which it had been read in the ancient Church about A.D. 380. |

[[Brooke Foss Westcott|Westcott]] and [[Fenton John Anthony Hort|Hort]], ''[[The New Testament in the Original Greek]]'' ([[1881 AD|1881]]). | [[Brooke Foss Westcott|Westcott]] and [[Fenton John Anthony Hort|Hort]], ''[[The New Testament in the Original Greek]]'' ([[1881 AD|1881]]). | ||

| - | The majority of textual critical scholars since the late 19th Century, have adopted an [[textual criticism#Eclecticism|eclectic]] approach to the [[Greek New Testament]]; with the most weight given to the earliest extant manuscripts which tend mainly to be [[Alexandrian text-type|Alexandrian]] in character; the resulting eclectic Greek text departing from the Textus Receptus in around 6,000 readings. A significant minority of textual scholars, however, maintain the priority of the [[Byzantine text-type]]; and consequently prefer the "[[Majority Text]]". No school of [[textual criticism|textual scholarship]] now continues to defend the priority of the Textus Receptus; although this position does still find adherents amongst the [[King-James-Only Movement]], and other [[Protestant]] groups hostile to the whole discipline of text criticism—as applied to scripture; and suspicious of any departure from [[Protestant Reformation|Reformation]] traditions. | + | The majority of textual critical scholars since the late 19th Century, have adopted an [[textual criticism#Eclecticism|eclectic]] approach to the [[Greek New Testament]]; with the most weight given to the earliest extant manuscripts which tend mainly to be [[Alexandrian text-type|Alexandrian]] in character; the resulting eclectic Greek text departing from the Textus Receptus in around 6,000 readings. A significant minority of textual scholars, however, maintain the priority of the [[Byzantine text-type]]; and consequently prefer the "[[Majority Text]]". No school of [[textual criticism|textual scholarship]] now continues to defend the priority of the Textus Receptus; although this position does still find adherents amongst the [[King-James-Only Movement]], and other independent [[Protestant]] groups hostile to the whole discipline of text criticism—as applied to scripture; and suspicious of any departure from [[Protestant Reformation|Reformation]] traditions. |

| + | |||

| + | == Criticism from KJVO == | ||

| + | ====[[Gail Riplinger]]==== | ||

| + | [[Gail Riplinger]] concerning [[Theodore Beza]] stated: | ||

| + | :The College of Cardinals has its counterpart at some otherwise good Christian colleges. There, the word of God must be corrected by a corrupt Greek text or a 16th century Greek text by a ‘Reformed’ five point Calvinist, such as [[Theodore Beza|Beza]], who took over the church at Geneva after [[John Calvin]] died. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :[[Theodore Beza|Beza]]’s extreme supralapsarian theology charges God with the origin of evil. That serious lack of discernment and other tiny lapses in his Greek text led the KJB translators to ignore his text where it did not follow the “Originall Greeke.” | ||

== Defense of the Textus Receptus == | == Defense of the Textus Receptus == | ||

[[Image:TR Logo.JPG|200px|thumb|left|Textus Receptus Logo in Stephanus' and Beza's editions]] | [[Image:TR Logo.JPG|200px|thumb|left|Textus Receptus Logo in Stephanus' and Beza's editions]] | ||

| - | [[Frederick von Nolan]], a 19th century historian and [[Greek]] and [[Latin]] scholar, spent 28 years attempting to trace the | + | [[Frederick von Nolan]], a 19th century historian and [[Greek]] and [[Latin]] scholar, spent 28 years attempting to trace the Textus Receptus to apostolic origins. He was an ardent advocate of the supremacy of the Textus Receptus over all other editions of the [[Greek New Testament]], and argued that the first editors of the printed [[Greek New Testament]] intentionally selected the texts they did because of their superiority and disregarded other texts which represented other text-types because of their inferiority. |

:It is not to be conceived that the original editors of the [Greek] New Testament were wholly destitute of plan in selecting those manuscripts, out of which they were to form the text of their printed editions. In the sequel it will appear, that they were not altogether ignorant of two classes of manuscripts; one of which contains the text which we have adopted from them; and the other that text which has been adopted by M. Griesbach. | :It is not to be conceived that the original editors of the [Greek] New Testament were wholly destitute of plan in selecting those manuscripts, out of which they were to form the text of their printed editions. In the sequel it will appear, that they were not altogether ignorant of two classes of manuscripts; one of which contains the text which we have adopted from them; and the other that text which has been adopted by M. Griesbach. | ||

| - | Regarding Erasmus | + | Regarding [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]], [[Frederick von Nolan|Nolan]] stated: |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | Regarding [[1 John 5:7]], the long-standing belief that MS. 61 was created specifically to force Erasmus to add the text is no longer considered a legitimate concern. Metzger himself admits this in the 3rd edition of ''The Text of the New Testament...'' when he notes (footnote 2 on p. 292): | + | :Nor let it be conceived in disparagement of the great undertaking of [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]], that he was merely fortuitously right. Had he barely undertaken to perpetuate the tradition on which he received the sacred text he would have done as much as could be required of him, and more than sufficient to put to shame the puny efforts of those who have vainly labored to improve upon his design. [...] With respect to Manuscripts, it is indisputable that he was acquainted with every variety which is known to us, having distributed them into two principal classes, one of which corresponds with the Complutensian edition, the other with the Vatican manuscript. And he has specified the positive grounds on which he received the one and rejected the other. |

| + | [[Image:Textus receptus.jpg|thumb|]] | ||

| + | Regarding [[1 John 5:7]], the long-standing belief that MS. 61 was created specifically to force [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] to add the text is no longer considered a legitimate concern. Metzger himself admits this in the 3rd edition of ''The Text of the New Testament...'' when he notes (footnote 2 on p. 292): | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| - | What was said about Erasmus promise and his subsequent suspicion that MS. 61 was written expressly to force him to [add [[1 John 5:7]] to the text], needs to be corrected in light of the research of H.J. de Jonge, a specialist in Erasmian studies who finds no explicit evidence that supports this frequently made assertion. | + | What was said about [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] promise and his subsequent suspicion that MS. 61 was written expressly to force him to [add [[1 John 5:7]] to the text], needs to be corrected in light of the research of H.J. de Jonge, a specialist in Erasmian studies who finds no explicit evidence that supports this frequently made assertion. |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| - | Textus Receptus was defended by [[John William Burgon|Burgon]] in his ''The Revision Revised'' (1881), by Edward Miller in ''A Guide to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament''. According to [[John William Burgon|Burgon]] [[Codex Alexandrinus]], and [[Codex Ephraemi]] are older than [[Codex Sinaiticus|Sinaiticus]], and [[Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209|Vaticanus]]. Peshitta originated from the 2nd century. Arguments of Miller were of the same kind. [[Edward Freer Hills|Hills]] took different point of view. Hills rejected text of majority (Byzantine text) and according to him Textus Receptus was the closest text to the autographs. He concluded that Erasmus was divinely guided when he introduced Latin Vulgate readings into his Greek text and argued for the authenticity of the Comma Johanneum. | + | Textus Receptus was defended by [[John William Burgon|Burgon]] in his ''The Revision Revised'' (1881), by Edward Miller in ''A Guide to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament''. According to [[John William Burgon|Burgon]] [[Codex Alexandrinus]], and [[Codex Ephraemi]] are older than [[Codex Sinaiticus|Sinaiticus]], and [[Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209|Vaticanus]]. Peshitta originated from the 2nd century. Arguments of Miller were of the same kind. [[Edward Freer Hills|Hills]] took different point of view. Hills rejected text of majority (Byzantine text) and according to him Textus Receptus was the closest text to the autographs. He concluded that [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]] was divinely guided when he introduced Latin Vulgate readings into his Greek text and argued for the authenticity of the Comma Johanneum. |

| - | [[ | + | ==Hebrew Textus Receptus== |

| + | |||

| + | In certain circles of scholarship the term Textus Receptus is defined as a reference to all Byzantine type texts, or to any reformation type Greek text, or sometimes to a specific edition of the Greek New Testament, such as the [[1598 AD|1598]] text of Beza, or the [[1550 AD|1550]] text of Stephanus, or other individual [[Greek]] [[New Testament]] editions. The [[Hebrew]] [[Masoretic Text]] has been called the Hebrew Textus Receptus, or simply the Hebrew received text, specifically referring to the [[Daniel Bomberg|Bomberg]] 1524-25 edition. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Textus Receptus Editions Online == | ||

| + | {{Textus_Receptus_Editions}} | ||

| + | ====[[Complutensian Polyglot]]==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[1514 AD|1514]]: [https://archive.org/details/ComplutensianPolyglotBibleOldTestamentNewTestament Archive] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====[[Desiderius Erasmus]]==== | ||

| + | * [[1516 AD|1516]] The Swiss [http://e-rara.ch/ e-rara.ch] has [http://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/content/titleinfo/895554 Erasmus’ <i>Novum Instrumentum omne</i> of 1516], with the <i>Annotationes</i>. From the [http://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/content/structure/895554 contents page], one can download PDF files of parts of the book. One can also download a PDF of the entire book. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is [http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb11059002-1 another copy] in the digital collections of the [http://www.bsb-muenchen.de/ Bayerische Staatsbibliothek] (Staatliche Bibliothek, Regensburg, shelf mark 999/2Script.238). | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is also a [http://books.google.com/books?id=gx9JAAAAcAAJ GB] version of the 1516 edition ([http://www.onb.ac.at/ Österreichische Nationalbibliothek], shelf mark 4.D.10). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yet [http://digital.ub.uni-duesseldorf.de/ihd/content/titleinfo/1344281 another, interesting copy];is found in the [http://www.ub.uni-duesseldorf.de/home/ Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf] (shelf mark ULBD DUE 01 α); it is from the collection of (first owner) Johannes Cincinnius von Lippstadt, who even noted on which day he bought the book, and how much he paid for it (see f. aaa 1v), and who made extensive use of it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[1519 AD|1519]] Erasmus’ [http://archive.thulb.uni-jena.de/hisbest/receive/HisBest_cbu_00002855 second edition of 1519] with the <i>Annotationes</i> is available at [http://e-rara.ch/ e-rara], but at the [http://www.uni-jena.de/ University of Jena]; it can also be downloaded as PDF. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[1522 AD|1522]] Erasmus’ [http://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/content/titleinfo/1240590 third edition of 1522], with the <i>Annotationes</i>, is available as well at e-rara. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[1527 AD|1527]] Erasmus’ [http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-2584 fourth edition of 1527], with the <i>Annotationes</i>, is available as well at e-rara. | ||

| + | The [http://digital.wlb-stuttgart.de/purl/bsz346133963 1527 volume with the <i>Annotationes</i>] is available in the Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[1535 AD|1535]] [http://www.erasmus.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=eol.getdetail&field1=id&value1=4900 Erasmus’ 1535 edition] can be found at the [http://www.erasmus.org/ Erasmus Centre for Early Modern Studies], but only the New Testament text, not the <i>Annotationes</i>. Previously the Centre used the DjVU format, but since 2014 it provides PDFs instead. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another copy can be found at GB: [http://books.google.com/books?id=mjBJAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover Text] and [https://books.google.nl/books?id=_jBJAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover <i>Annotationes</i>] (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, shelf mark 4.O.18). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''List compiled from [http://vuntblog.blogspot.nl/2010/11/erasmus-1516-edition-online.html the Amsterdam NT Weblog]'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Colinæus==== | ||

| + | * [[1534 AD|1534]] [http://confessionalbibliology.com/PDFs/Colines%201534%20Greek%20NT.pdf PDF]<small>([[Simon de Colines]])</small> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Stephanus ([[Robert Estienne]])==== | ||

| + | * [[1546 AD|1546]] ''Τῆς καινῆς διαθήκης ἅπαντα. Novum Testamentum. Ex bibliotheca regia'' (Paris: Robertus Stephanus). [https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31175031506309;view=1up;seq=11 Hathi Trust] | ||

| + | :Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 1.L.29: [http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ119528906&order=919&view=SINGLE ÖNB] | [https://books.google.com.au/books?id=bMRIAAAAcAAJ&redir_esc=y GB] | ||

| + | :Regensburg, Staatliche Bibliothek, 999/Script.7: [https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/urn/resolver.php?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb11116067-2 MDZ] | ||

| + | * [[1549 AD|1549]] ''Τῆς καινῆς διαθήκης ἅπαντα. Novum Testamentum. Ex bibliotheca regia'' (Paris: Robertus Stephanus). | ||

| + | :Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 1.L.34: [http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ119529406&order=919&view=SINGLE ÖNB] | ||

| + | :Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, BIB.TH.003654: [https://books.google.com.au/books?vid=GENT900000097759&redir_esc=y GB] | ||

| + | * [[1550 AD|1550]] ''Τῆς καινῆς διαθήκης ἅπαντα. Novum Iesu Christi D. N. Testamentum. Ex bibliotheca regia'' (Paris: Robertus Stephanus, 1550). [http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?pid=d-3159372 Microfilm] | ||

| + | :Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 4.D.25: [http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ119580709&order=494&view=SINGLE ÖNB] | ||

| + | :WWU Münster, Bibelmuseum, H 1550: [https://sammlungen.ulb.uni-muenster.de/urn/urn:nbn:de:hbz:6:1-301539 Bibelmuseum] | ||

| + | :Regensburg, Staatliche Bibliothek, 999/2Script.67: [https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de//resolve/display/bsb11058944.html MDZ] | ||

| + | :[provenance unclear]: [http://www.csntm.org/PrintedBook/ViewBook/RobertusStephanusNovumTestamentum1550 CSNTM] (pages with biblical text only; good resolution; no navigation) | ||

| + | * [[1551 AD|1551]] ''Ἅπαντα τῆς καινῆς διαθήκης. Novum Iesu Christi D. N. Testamentum. Cum duplici interpretatione, D. Erasmi, et Veteris interpretis: Harmonia item Euangelica, et copioso indice'' (Geneva: Robertus Stephanus, 1551). | ||

| + | :Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, BIB.ACC.016001: [https://books.google.com.au/books?vid=GENT900000080653&redir_esc=y GB (vol. 1)]; [https://books.google.be/books?vid=GENT900000078494 GB (vol. 2)] | ||

| + | :Bibliothèque de Genève, Bb 2299: [https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-6036 e-rara] | ||

| + | :Assisi, Pro civitate museum, Cinquecentina 13-1 and 13-2: [http://procivitate.assisi.museum/web/cinquecentine.aspx?ccid=14827 PCM (vol. 1)]; [http://procivitate.assisi.museum/web/cinquecentine.aspx?id=15293 PCM (vol. 2)] | ||

| + | :Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, Th B IV 17: [https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de//resolve/display/bsb11283864.html MDZ (vol 1)]; [https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de//resolve/display/bsb11283865.html MDZ (vol. 2)] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''List compiled from [https://vuntblog.blogspot.com/2020/04/robertus-stephanus-greek-new-testament.html?fbclid=IwAR3CYL1r1k8sQmSinwQ_K-CCT-ALos127bIIyIRr1-ZXQpABj94zIoXraMA the Amsterdam NT Weblog]'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====[[Theodore Beza]]==== | ||

| + | ;Major editions | ||

| + | * 1. [[1556 AD|1556]]/[[1557 AD|57]] [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1751840 e-rara] (Beza’s NT in Volume 2, from [541] onwards); [http://books.google.com/books?id=A0usDcgwzc8C GB] and [http://books.google.com/books?id=e5dUAAAAcAAJ GB] (a better copy) | ||

| + | * 2. [[1565 AD|1565]] [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1751933 e-rara]. | ||

| + | * 3. [[1582 AD|1582]] [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1752205 e-rara]. | ||

| + | * 4. [[1588 AD|1588]]/[[1589 AD|89]] [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/2833077 e-rara]; [http://www.csntm.org/printedbook/viewbook/TestamentumNovum CSNTM]; [http://archive.org/details/testamentvmnovvm00bzet IA]; [http://books.google.nl/books?id=tt1TAAAAcAAJ GB]. | ||

| + | * 5. [[1598 AD|1598]] [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1752610 e-rara]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Special cases | ||

| + | * [[1559 AD|1559]]: unauthorised Basel edition: [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1751868 e-rara]; [http://dfg-viewer.de/show/?id=8071&tx_dlf%5Bid%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fdigitale.bibliothek.uni-halle.de%2Foai%2F%3Fverb%3DGetRecord%26metadataPrefix%3Dmets%26identifier%3D993514&tx_dlf%5Bpage%5D=1 ULB Sachsen-Anhalt]. | ||

| + | * [[1563 AD|1563]]: Beza’s <i>Responsio</i> against Castellio (referred to on the title page of the 1565 edition): [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/859334 e-rara] | ||

| + | * [[1565 AD|1565]]: a special copy with Beza’s own handwritten notes in preparation of the third edition (MHR O4 cd (565) a): [http://doc.rero.ch/record/18245?ln=fr réro]. | ||

| + | * [[1569 AD|1569]]: Tremellius’; Syriac NT, with Beza’s Greek and Latin text included: [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1751977 e-rara] (both volumes); [http://books.google.com/books?id=eY61MnibT1QC GB (Matt-John)]. | ||

| + | * [[1594 AD|1594]]: the <i>Annotationes</i> printed separately: [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/976558 e-rara]. | ||

| + | * [[1642 AD|1642]]: the Cambridge edition, with Camerarius’ commentary: [http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2003&res_id=xri:eebo&rft_id=xri:eebo:citation:9292058 EEBO (limited access)]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Minor editions | ||

| + | * 1. [[1565 AD|1565]]: [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1751934 e-rara] | ||

| + | * 2. [[1567 AD|1567]]: [http://www.e-rara.ch/mhr_g/content/titleinfo/3930535 e-rara] | ||

| + | * 3. [[1580 AD|1580]]: [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1752139 e-rara]; [http://books.google.com/books?id=vr9IAAAAcAAJ GB] | ||

| + | * 4. [[1590 AD|1590]]: [http://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/titleinfo/1752374 e-rara] | ||

| + | * 5. [[1604 AD|1604]]: [http://books.google.com/books?id=NhY-AAAAcAAJ GB (vol. 1)] [http://books.google.com/books?id=QBY-AAAAcAAJ GB (vol. 2)]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Other | ||

| + | * [[1575 AD|1575]]: a Latin-only edition which introduces Chapter summaries: [http://books.google.nl/books?id=DsBIAAAAcAAJ GB] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Plantin Polyglot==== | ||

| + | * [[1584 AD|1584]]: [https://books.google.com.au/books?id=QAdfiWV009YC&redir_esc=y GB] | ||

| + | |||

| + | :''List compiled with help from the [http://vuntblog.blogspot.co.uk/2012/11/bezas-new-testament-editions-online.html the Amsterdam NT Weblog].'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Elzevir==== | ||

| + | * [[1624 AD|1624]] [https://www.originalbibles.com/PDF_Downloads/Testamentum_novum_graece_ex_reguus_aliis_1624_Elzevir.pdf PDF] | ||

| + | * [[1633 AD|1633]] (Elzevir) edited by [[Jeremias Hoelzlin]], Professor of Greek at Leiden. | ||

| + | * [[1641 AD|1641]] (Elzevir) | ||

| + | * [[1678 AD|1679]] (Elzevir) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Scholz==== | ||

| + | * [[1841 AD|1841]] <small>([[Johann Martin Augustin Scholz|Scholz]])</small> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Scrivener==== | ||

| + | * [[1881 AD|1881]] [http://textus-receptus.com/files/Scrivener-1881.pdf Scan of The Greek New Testament - Textus Receptus by Scrivener]<small>(Η ΚΑΙΝΗ ΔΙΑΘΗΚΗ)</small> See also ~ [[191 Variations in Scrivener’s 1881 Greek New Testament from Beza's 1598 Textus Receptus]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == English translations of the Textus Receptus== | ||

| + | * Tyndale New Testament 1526-1530 | ||

| + | * Miles Coverdale's Bible 1535 | ||

| + | * Matthew's Bible 1537 | ||

| + | * The Great Bible 1539 | ||

| + | * [[Geneva Bible]] 1557-1560 | ||

| + | * The [[Bishops' Bible]] 1568 | ||

| + | * [[King James Version]] 1611,1613,1629,1664,1701,1744,1762,1769,1850 | ||

| + | * Quaker Bible English 1764 | ||

| + | * Webster Bible 1833 | ||

| + | * [[Youngs Literal Version]] 1862 | ||

| + | * Julia E. Smith Parker Translation 1876 | ||

| + | * Darby Bible 1884,1890 | ||

| + | * Interlinear KJV Parallel New Testament in Greek and English – by George R. Berry | ||

| + | * [[New King James Version]] 1982 | ||

| + | * The Interlinear Bible by Jay P. Green, Sr. 1986 | ||

| + | * The Scriptures 1993, 1998, 2009 | ||

| + | * The 21st Century King James Version 1994 | ||

| + | * [[Green's Literal Translation|Literal Translation of the Bible]] 1995 | ||

| + | * Tyndale's New Testament edited by David Daniell 1995 | ||

| + | * Third Millennium Bible 1998 | ||

| + | * [[Modern King James Version]] 1999 | ||

| + | * Analytical Literal Translation 1999 | ||

| + | * Updated King James Version 2000 | ||

| + | * King James Version with Apocrypha by David Norton 2005 | ||

| + | * Holy Bible in Hebrew and Greek By Ryan Handermann | ||

| + | * AV7 The New Authorized Version of the Holy Bible in Present-day English (The AV7 Bible | ||

| + | * The Holy Bible Lighthouse Version By David Plaisted | ||

| + | * Holy Scriptures V-W Edition 2010 | ||

| + | * Mickelson's Hilkiah Edition New Testament Interlinear : An English Translation interlined with the Hebraic-Koine Greek of the Textus Receptus, the 1550 Stephanus (Hebrew Edition) | ||

| + | * Yah Bible KJV by Daniel Merrick, 2010 | ||

| + | * Real - New Testament By Hadarel Corporation | ||

| + | * King James Version Easy Reader 2010 | ||

| + | * 1599 Geneva Bible by Tolle Lege Press 2010 | ||

| + | * Jesus' Disciples Bible 2012 | ||

| + | * The Revised Young's Literal Translation 2012 | ||

| + | * The Names of God Bible (KJV) by Ann Spangler 2013 | ||

| + | * DIVINE NAME KING JAMES BIBLE (2011) | ||

| + | * Proper Name Version of the King James Bible | ||

| + | * Jubilee Bible 2000 2013 | ||

| + | * Besorah Of Yahusha Natsarim Version | ||

| + | * The Complete Koine-English Reference Bible: New Testament, Septuagint and Strong's Concordance Kindle Edition 2014 by Joshua Dickey | ||

| + | * [[Modern English Version]] 2014 | ||

| + | * The New Testament Textus Receptus Edition Paperback – April 7, 2015 by Christopher Vaughan | ||

| + | * [[King James Version 2016]] | ||

| + | * [[Simplified King James Version]] | ||

| + | * [[King James Version 2023]] | ||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 88: | Line 374: | ||

* [[Novum Instrumentum omne]] | * [[Novum Instrumentum omne]] | ||

* [[Theodore Beza]] | * [[Theodore Beza]] | ||

| + | * [[Dean Burgon Society]] | ||

| + | * [[Desiderius Erasmus]] | ||

| + | * [[Robert Estienne]] | ||

| + | * [[Theodore Beza]] | ||

| + | * [[Article: The Word of God for All Nations by Phil Stringer|The Word of God for All Nations]] by [[Phil Stringer]] A massive list of bibles, based upon the [[Textus Receptus]] | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 95: | Line 386: | ||

* [[Edward F. Hills]], [[The King James Bible Defended]] ISBN: 0-915923-00-9 | * [[Edward F. Hills]], [[The King James Bible Defended]] ISBN: 0-915923-00-9 | ||

| + | * [http://www.kjvtoday.com/home/reliable-greek-text Reliable Greek Text] by [[KJV Today]] | ||

| + | * [http://www.deanburgonsociety.org/DeanBurgon/dbs2771.htm Summary of The Traditional Text] by [[Dean John William Burgon]] | ||

| + | * [http://www.deanburgonsociety.org/DeanBurgon/dbs0804.htm Burgon's Warnings on Revision of the Textus Receptus and the King James Bible] | ||

| + | '''Modern Textual Criticism''' | ||

| - | + | (Many of the arguments against the TR in the books below are filled with slander and errors) | |

| - | + | ||

* S. P. Tregelles, ''The Printed Text of the Greek New Testament'', London 1854. | * S. P. Tregelles, ''The Printed Text of the Greek New Testament'', London 1854. | ||

* Bruce M. Metzger, B. D. Ehrman, ''The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration'', [[Oxford University Press]], 2005. | * Bruce M. Metzger, B. D. Ehrman, ''The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration'', [[Oxford University Press]], 2005. | ||

* W. W. Combs, ''Erasmus and the textus receptus'', DBSJ 1 (Spring 1996). | * W. W. Combs, ''Erasmus and the textus receptus'', DBSJ 1 (Spring 1996). | ||

| - | * Daniel B. Wallace, ''Some Second Thoughts on the Majority Text''. ''[[Bibliotheca Sacra]]'' '''146''' (1989): 270-290. | + | * [[Daniel Wallace|Daniel B. Wallace]], ''Some Second Thoughts on the Majority Text''. ''[[Bibliotheca Sacra]]'' '''146''' (1989): 270-290. |

* Dr [[James White]]. ''King James Only Controversy, Can You Trust the Modern Translations?'' Bethany House, 1995. | * Dr [[James White]]. ''King James Only Controversy, Can You Trust the Modern Translations?'' Bethany House, 1995. | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| - | * [http://www. | + | * [http://textusreceptusbibles.com/Editorial/Textus_Receptus Textus Receptus Bibles - Overview of the Textus Receptus] |

| - | * [http://www.wayoflife.org/ | + | * [http://textusreceptusbibles.com/Document/History Textus Receptus Bibles - History of the Textus Receptus] |

| + | * [http://textusreceptusbibles.com/Editorial/TRAuthors Textus Receptus Bibles - The Men Who Wrote the Textus Receptus] | ||

| + | * [http://textusreceptusbibles.com/Document/Differences_Between_Textus_Receptus_and_NaUbs Important Differences Between the Textus Receptus and the Nestle Aland/United Bible Society Text] | ||

| + | * [http://www.tbsbibles.org/pdf_information/202-1.pdf A Brief Look at the Textus Receptus] | ||

| + | * [http://www.wayoflife.org/database/is_the_received_text_based_on_few.html Is the Received Text Based on a Few Late Manuscripts? ] | ||

* [http://www.angelfire.com/la2/prophet1/erasmus.html Little known facts about Erasmus and the Scriptures] | * [http://www.angelfire.com/la2/prophet1/erasmus.html Little known facts about Erasmus and the Scriptures] | ||

| + | * [http://www.bibles-online.net/1519/ Scan of Erasmus' 1519 Greek/Latin New Testament] | ||

| + | * [http://www.bibles-online.net/1521/ Scan of Erasmus' 1522 Greek/Latin New Testament] | ||

| + | * [http://www.bibles-online.net/1550/ Scan of the 1550 Stephanus Greek NT] | ||

| + | * [http://www.temcat.com/L-4-Reference-Library/Reference/TRStephanus.pdf The Greek New Testament - Stephanus 1550 PDF] | ||

| + | * [http://www.csntm.org/printedbook/viewbook/TestamentumNovum Scan of the 1588 Testamentum Novum by Theodore Beza] | ||

| + | * [http://textus-receptus.com/files/Beza-1598.pdf Scan of The Greek New Testament - Textus Receptus by Theodore Beza - 1598 PDF] | ||

| + | * [http://www.bibles-online.net/hutter/ Scan of the 1599 Hutter Polyglot] | ||

| + | * [http://www.thefishersofmenministries.com/English%20Hexapla%20676.pdf English Hexapla PDF] | ||

| + | * [http://bible.zoxt.net/hex/hex.htm English Hexapla Pictures] | ||

| + | * [http://www.libertyparkusafd.org/lp/Burgon/electronic%20books/Greek%20New%20Testament%20(Textus%20Receptus)%20Scrivener%201894.pdf Scriveners Textus Receptus PDF] | ||

| + | * [http://books.google.com/books?id=nZ0NAAAAYAAJ&pg=pl#PPA13,M1 ''Hē Kainē Diathēkē: Novum Testamentum textu︢s Stephanici A.D. 1550'' (1860)] by Scrivener | ||

* [http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textus_Receptus Wikipedia Article on the Textus Receptus] | * [http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textus_Receptus Wikipedia Article on the Textus Receptus] | ||

| + | * [http://www.jeffriddle.net/2018/10/wm-105-full-armor-radio-interview-text.html WM 105: Full Armor Radio Interview: Text of the NT] by [[Jeff Riddle]] | ||

[[Category:Greek New Testament]] | [[Category:Greek New Testament]] | ||

| Line 115: | Line 425: | ||

[[Category:Early printed bibles]] | [[Category:Early printed bibles]] | ||

[[Category:Books by Desiderius Erasmus]] | [[Category:Books by Desiderius Erasmus]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Donate}} | ||

Current revision

Textus Receptus (Latin: "received text") is the name subsequently given to the succession of printed Greek texts of the New Testament which constituted the translation base for the original German Luther Bible, for the translation of the New Testament into English by William Tyndale, the King James Version, and for most other Reformation-era New Testament translations throughout Western and Central Europe. The series flowed from both the Byzantine and Latin traditional texts, and the first printed Greek New Testament was the Complutensian Polyglot in 1514 which was not published until eight years later. The second Greek New Testament printed and published in 1516 called the Greek New Testament; a work undertaken in Basel by the Dutch scholar and Christian humanist Desiderius Erasmus. Erasmus did not "invent" the Textus Receptus, but merely printed a small collection of what was already the vast majority of New Testament Manuscripts.

Erasmus had devoted at least 15 years to the initial project, studying and collecting manuscripts from all over Europe. He had collated many Greek New Testament manuscripts and was surrounded by several language translations and also a multitude of verses from the commentaries and writings of Origen, Cyprian, Ambrose, Basil, Chrysostom, Cyril, Jerome, and Augustine. Erasmus had access to Codex Vaticanus and Codex Bezae, but rejected most of the readings of Vaticanus as corrupt, as did the King James Translators. The text Erasmus chose had an outstanding history in the Greek, Syrian and Waldensian churches. Robert Estienne and Theodore Beza continued Erasmus' work and it became the standard Greek New Testament text.

Pre-16th Century

Textus Receptus type manuscripts and versions have existed as the majority of texts for almost 2000 years. Frederick von Nolan spent 28 years tracing the Textus Receptus to apostolic origins. John William Burgon supported his arguments with the opinion that the Codex Alexandrinus and Codex Ephraemi, were older than the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus; and also that the Peshitta translation into Syriac (which supports the Byzantine Text), originated in the 2nd century around 150 A.D.. Papyrus 66 used the Textus Receptus. The 157 A.D. Italic Church in the Northern Italy used the Textus Receptus. The 177 A.D. Gallic Church of Southern France used the Textus Receptus. The Celtic Church used the Textus Receptus. The Waldensians used the Textus Receptus. The Gothic Version of the 4th or 5th century used the Textus Receptus. The Curetonian Syriac is basically the Textus Receptus. Vetus Itala is from Textus Receptus. Codex Washingtonianus of Matthew used the Textus Receptus. Codex Alexandrinus in the Gospels used the Textus Receptus. 99% of extant New Testament manuscripts all used the Textus Receptus. The Greek Orthodox Church used the Textus Receptus.

Greek manuscript evidences point to a Byzantine/Textus Receptus majority. 85% of papyri used Textus Receptus, only 13 represent text of Westcott and Hort. 97% of uncial manuscripts used Textus Receptus, only 9 manuscripts used text of Westcott and Hort. 99% of minuscule manuscripts used Textus Receptus, only 23 used text WH. 100% of lectionaries used the Textus Receptus.

Received Text

The origin of the term "Textus Receptus" comes from the publisher's preface to the 1633 edition produced by Abraham Elzevir and his nephew Bonaventure who were printers at Leiden:

- Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum: in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus. Translated "so you hold the text, now received by all, in which nothing corrupt."

The two words, textum and receptum, were modified from the accusative to the nominative case to render textus receptus. Over time, this term has been retroactively applied to Erasmus' editions, as his work served as the basis of the others. The term "Textus Receptus" has also been used to refer to the early church fathers quotes containing "Textus Receptus" type readings, and it is also used as a synonym for Byzantine type texts, the Majority Text, and any reading that is supportive of the Textus Receptus used to underlie the King James Version. Unlike the editions of Erasmus, Estienne (Stephanus), and Beza before them, the Elzevirs were not editors of the editions attributed to them, only the printers. The 1633 edition was edited by Jeremias Hoelzlin, Professor of Greek at Leiden.

William Fulke (1538-1589) used the term "received text" in his book Defense of the Sincere and True Translations (Fulke's 49th response), to describe the Latin and also the commonly accepted texts in certain ages.

Verses about receiving the words of God

Matthew 13:

- 19 When any one heareth the word of the kingdom, and understandeth it not, then cometh the wicked one, and catcheth away that which was sown in his heart. This is he which received seed by the way side.

- 20 But he that received the seed into stony places, the same is he that heareth the word, and anon with joy receiveth it;

- 21 Yet hath he not root in himself, but dureth for a while: for when tribulation or persecution ariseth because of the word, by and by he is offended.

- 22 He also that received seed among the thorns is he that heareth the word; and the care of this world, and the deceitfulness of riches, choke the word, and he becometh unfruitful.

- 23 But he that received seed into the good ground is he that heareth the word, and understandeth it; which also beareth fruit, and bringeth forth, some an hundredfold, some sixty, some thirty.

John 10:18:

- No man taketh it from me, but I lay it down of myself. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again. This commandment have I received of my Father.

Acts 2:41:

- Then they that gladly received his word were baptized: and the same day there were added unto them about three thousand souls.

Acts 7:38:

- This is he, that was in the church in the wilderness with the angel which spake to him in the mount Sina, and with our fathers: who received the lively oracles to give unto us:

Acts 7:53:

- Who have received the law by the disposition of angels, and have not kept it.

Acts 8:14:

- Now when the apostles which were at Jerusalem heard that Samaria had received the word of God, they sent unto them Peter and John:

Acts 11:1:

- And the apostles and brethren that were in Judaea heard that the Gentiles had also received the word of God.

Acts 17:11:

- These were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of mind, and searched the scriptures daily, whether those things were so.

1 Corinthians 15:3:

- For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures;

Galatians 1:9:

- As we said before, so say I now again, If any man preach any other gospel unto you than that ye have received, let him be accursed.

1 Thessalonians 1:6:

- And ye became followers of us, and of the Lord, having received the word in much affliction, with joy of the Holy Ghost:

1 Thessalonians 2:13:

- For this cause also thank we God without ceasing, because, when ye received the word of God which ye heard of us, ye received it not as the word of men, but as it is in truth, the word of God, which effectually worketh also in you that believe.

Hebrews 7:11:

- If therefore perfection were by the Levitical priesthood, (for under it the people received the law,) what further need was there that another priest should rise after the order of Melchisedec, and not be called after the order of Aaron?

2 Peter 1:17:

- For he received from God the Father honour and glory, when there came such a voice to him from the excellent glory, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.

2 John 1:4:

- I rejoiced greatly that I found of thy children walking in truth, as we have received a commandment from the Father.

Revelation 3:3:

- Remember therefore how thou hast received and heard, and hold fast, and repent. If therefore thou shalt not watch, I will come on thee as a thief, and thou shalt not know what hour I will come upon thee.

History of the Printed Textus Receptus

Complutensian Polyglot

See Also Complutensian Polyglot

The Complutensian Polyglot is the name given to the first printed polyglot of the entire Bible, initiated and financed by Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros. It contained the first printed Greek New Testament. Although the New Testament was printed in 1514 its release was delayed until the Old Testament was completed in 1517. By this time Erasmus had printed his Novum Instrumentum omne and obtained an exclusive four-year publishing privilege from Emperor Maximilian and Pope Leo X in 1516. Because of Erasmus' exclusive privilege, publication of the Polyglot was delayed until Pope Leo X could sanction it in 1520. It is believed to have not been distributed widely before 1522. It included the first printed editions of the Greek New Testament, the complete Septuagint, and the Targum Onkelos. It came as a six-volume set. The first four volumes contains the Old Testament. Each page consists of three parallel columns of text: Hebrew on the outside, the Latin Vulgate in the middle, and the Greek Septuagint on the inside. On each page of the Pentateuch, the Aramaic text (the Targum Onkelos) and its own Latin translation are added at the bottom. The fifth volume, the New Testament, consists of parallel columns of Greek and the Latin Vulgate. The sixth volume contains various Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek dictionaries and study aids. The Complutensian Polyglot remains as a strong witness against those textual critics who claim Erasmus "invented" the Textus Receptus as most of the readings are akin to Erasmus' editions of the Greek New Testament.

Novum Instrumentum omne

See Also Novum Instrumentum omne

Erasmus had been working for years on two projects: a collation of Greek texts and a fresh Latin New Testament. In 1512, he began his work on a fresh Latin New Testament. He collected all the Vulgate manuscripts he could find to create a critical edition. Then he polished the Latin. He declared, "It is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better Latin." Erasmus was keen to amend the old Vulgate and poured his life into the project: "My mind is so excited at the thought of emending Jerome’s text, with notes, that I seem to myself inspired by some god. I have already almost finished emending him by collating a large number of ancient manuscripts, and this I am doing at enormous personal expense."

While his intentions for publishing a fresh Latin translation are clear, it is less clear why he included the Greek text. Though some speculate that he intended on producing a critical Greek text or that he wanted to beat the Complutensian Polyglot into print, there is no evidence to support this. Rather his motivation seems to be simpler: he included the Greek text to prove the superiority of his Latin version. He wrote,

- "There remains the New Testament translated by me, with the Greek facing, and notes on it by me."

Erasmus, who had worked as a scribe himself, further demonstrated the reason for the inclusion of the Greek text when defending his work:

- "But one thing the facts cry out, and it can be clear, as they say, even to a blind man, that often through the translator’s clumsiness or inattention the Greek has been wrongly rendered; often the true and genuine reading has been corrupted by ignorant scribes, which we see happen every day, or altered by scribes who are half-taught and half-asleep."

Erasmus's new work was published by Froben of Basel in 1516 and thence became the first published Greek New Testament, the Novum Instrumentum omne, diligenter ab Erasmo Rot. Recognitum et Emendatum. The first Greek edition included Erasmus’ edited Latin text. Erasmus was surrounded with Bible manuscripts from his childhood in the 1460s, until the publication of his Greek Text in 1516. This is over 40 years! He worked for a dozen years on the text itself. “The preparation had taken years” (Durant, p. 283).

He used manuscripts: 1, 1rK, 2e, 2ap, 4ap, 7, 817.

Scrivener wrote:

- the colophon at the end of Erasmus' first edition, a large folio of 1,027 pages in all, is dated February, 1516 ; the end of the Annotations, March 1, 1516 ; Erasmus' dedication to Leo X, Feb. 1, 1516 ; and Froben's Preface, full of joyful hope and honest pride in the friendship of the first of living authors, Feb. 24, 1516. [1]

Novum Testamentum omne

See Also Novum Testamentum omne

The second edition used the more familiar term Testamentum instead of Instrumentum, and eventually became a major source for Luther's German translation. In second edition (1519) Erasmus acquired also Minuscule 3.

With the third edition of Erasmus' Greek text (1522) the Comma Johanneum was included, because a single 16th-century Greek manuscript (Codex Montfortianus) had subsequently been found to contain it, though Erasmus had expressed doubt as to the authenticity of the passage in his Annotations. Popular demand for Greek New Testaments led to many authorized and unauthorized editions in the early sixteenth century; almost all of which were based on Erasmus's work and incorporated his particular readings, although typically also making a number of minor changes of their own.