Caspar René Gregory

From Textus Receptus

(→External links) |

(→Life) |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

Gregory became Professor of Textual Criticism of the New Testament at the modernistic University of Leipzig, and he worked with Ezra Abbot in Germany (The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1908, Vol. II, p. 109). Gregory and Abbot completed the work Constantine Tischendorf left behind at his death (Schaff-Herzog, vol. II, p. 109) and reissued the eighth edition of Tischendorf’s New Testament with critical notes. Gregory was planning a ninth edition of Tischendorf’s New Testament, but he was killed in World War I fighting on the side of Germany. | Gregory became Professor of Textual Criticism of the New Testament at the modernistic University of Leipzig, and he worked with Ezra Abbot in Germany (The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1908, Vol. II, p. 109). Gregory and Abbot completed the work Constantine Tischendorf left behind at his death (Schaff-Herzog, vol. II, p. 109) and reissued the eighth edition of Tischendorf’s New Testament with critical notes. Gregory was planning a ninth edition of Tischendorf’s New Testament, but he was killed in World War I fighting on the side of Germany. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Quotes== | ||

| + | Gregory’s unbelief is witnessed by the following quotes from his writings: | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Christianity has not grown to be what it is, has not maintained itself and enlarged itself, by reason of books being read, no, not even by reason of the Bible’s being read from generation to generation” (Caspar Gregory, The Canon and Text of the New Testament, 1907, p. 44). | ||

| + | |||

| + | “THE EARLIEST CHRISTIAN AUTHORS DID NOT FOR AN INSTANT SUPPOSE THAT THEY WERE WRITING SACRED BOOKS” (Gregory, The Canon and Text of the New Testament, p. 49). | ||

| + | |||

| + | “THE LETTERS THAT THE APOSTLES WROTE TO THEM WERE NOT ‘BIBLE’” (Gregory, The Canon and Text of the New Testament, p. 55). | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is important to note that Bible believers of the 19th century did not accept the modern critical Greek text and many critiques were published to refute the theories of textual criticism. We have documented this in the book For Love of the Bible. The eager acceptance of the critical text was largely limited in that day to theological modernists and Unitarians. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By 1917, Francis Pieper, a conservative German Lutheran theologian, wrote: “During one period of the Arian controversy it was said that the world had become Arian. TODAY IT CAN BE SAID THAT THE SO-CALLED PROTESTANT WORLD HAS BECOME UNITARIAN” (Pieper, Christian Dogmatics, I, p. 421, translated from the German of 1917). | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is an interesting statement in light of the Unitarian influence within modern textual criticism and the wholesale modification of Trinitarian passages such as the following in the modern versions: | ||

== Notes and references == | == Notes and references == | ||

Revision as of 13:57, 8 March 2016

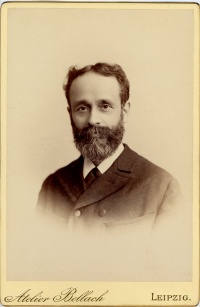

Caspar René Gregory (November 6, 1846 in Philadelphia – April 9, 1917 in a field hospital in Neuchâtel sur Aisne, France) was a German-American theologian. An American by birth but German by choice. Gregory was a Unitarian. He was the pupil of Unitarian Ezra Abbot at Harvard and was the son-in-law to Unitarian Joseph Thayer.

Contents |

Life

Gregory studied theology at two Presbyterian seminaries: in 1865-67 at the University of Pennsylvania and at Princeton Theological Seminary. In 1873, he decided to continue his studies at the University of Leipzig under Constantin von Tischendorf, whose work on textual criticism of the New Testament he had been referred to by his teacher, Ezra Abbot. He administered the scientific legacy of Tischendorf, who died in 1874, and continued his work.

Gregory completed his post-doctoral work in Leipzig in 1884, became an associate professor in 1889 and full honorary professor in 1891. In 1876, he obtained his PhD. with a dissertation on Gregorè the priest and the revolutionist. The first examiner for it was the historian, Georg Voigt (Todte, Georg Voigt, p. 111). The doctoral files in the university archive in Leipzig state the same. Gregory apparently had several doctorate degrees. Karl Josef Friedrich (p. 130) even mentions five doctorates in his biography of Gregory. At least one doctorate in theology obtained in Leipzig in 1889 is attested.

In August 1914, the German-American Gregory, who had been a citizen of Saxony since 1881, enlisted in the German army as the oldest wartime volunteer. He became a second lieutenant in 1916 and fell in 1917 on the western front.

Gregory specialized in New Testament textual criticism. He organized biblical manuscripts into a classification system (Die griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments, 1908) which is the system in use throughout the scholarly world today. He is also credited with being the first to notice the consistent medieval practice (called Gregory's Law) of collating parchment leaves so that grain side faced grain side and flesh side flesh side. He was also interested in biblical canon.

Gregory performed important service in the research of New Testament manuscripts and in textual criticism of the New Testament. It can even be said that the study of New Testament manuscripts was co-founded by Tischendorf and Gregory.

Besides his work, he is remembered by a memorial stone with a portrait in relief in Leipzig on Naunhofer Straße in front of the new Nickolai School in the Stötteritz part of the city, as well as a small square nearby.

Gregory became Professor of Textual Criticism of the New Testament at the modernistic University of Leipzig, and he worked with Ezra Abbot in Germany (The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1908, Vol. II, p. 109). Gregory and Abbot completed the work Constantine Tischendorf left behind at his death (Schaff-Herzog, vol. II, p. 109) and reissued the eighth edition of Tischendorf’s New Testament with critical notes. Gregory was planning a ninth edition of Tischendorf’s New Testament, but he was killed in World War I fighting on the side of Germany.

Quotes

Gregory’s unbelief is witnessed by the following quotes from his writings:

“Christianity has not grown to be what it is, has not maintained itself and enlarged itself, by reason of books being read, no, not even by reason of the Bible’s being read from generation to generation” (Caspar Gregory, The Canon and Text of the New Testament, 1907, p. 44).

“THE EARLIEST CHRISTIAN AUTHORS DID NOT FOR AN INSTANT SUPPOSE THAT THEY WERE WRITING SACRED BOOKS” (Gregory, The Canon and Text of the New Testament, p. 49).

“THE LETTERS THAT THE APOSTLES WROTE TO THEM WERE NOT ‘BIBLE’” (Gregory, The Canon and Text of the New Testament, p. 55).

It is important to note that Bible believers of the 19th century did not accept the modern critical Greek text and many critiques were published to refute the theories of textual criticism. We have documented this in the book For Love of the Bible. The eager acceptance of the critical text was largely limited in that day to theological modernists and Unitarians.

By 1917, Francis Pieper, a conservative German Lutheran theologian, wrote: “During one period of the Arian controversy it was said that the world had become Arian. TODAY IT CAN BE SAID THAT THE SO-CALLED PROTESTANT WORLD HAS BECOME UNITARIAN” (Pieper, Christian Dogmatics, I, p. 421, translated from the German of 1917).

This is an interesting statement in light of the Unitarian influence within modern textual criticism and the wholesale modification of Trinitarian passages such as the following in the modern versions:

Notes and references

- 1. Avrin, Leila (1991). Scribes, script, and books: the book arts from antiquity to the Renaissance. Chicago; London: American Library Association; The British Library. pp. 213. ISBN 9780838905227.

Works

- Prolegomena zu Tischendorfs Novum Testamentum Graece (editio VIII. critica major), 2 Vols., 1884-94 (German revised edition: text criticism of the NT, 3 Vols., 1900-09).

- Canon and Text of the New Testament, Edinburgh 1907.

- Das Freer-Logion, 1908.

- Die griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments, Leipzig 1908.

- Einleitung in das Neue Testament, 1909

- Vorschläge für eine kritische Ausgabe des griechischen Neuen Testaments, 1911.

- Die Koridethi-Evangelien, 1913.

- Zu Fuß in Bibellanden, publ. by Hermann Guthe, 1919.

- journal articles

- "The Essay 'Contra Novatianum'". The American Journal of Theology 3 (1899): 566–570.

Literature

- Karl Josef Friedrich: Caspar Rene Gregory, in: Sächsische Lebensbilder, Vol. I, Dresden 1930, p. 125-131.

- Jünger, Ernst (Publ.): Caspar René Gregory, in: Die Unvergessenen. München 1928, p. 111ff.