Codex Sangallensis 48

From Textus Receptus

(→Gallery) |

(→Gallery) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

== Gallery == | == Gallery == | ||

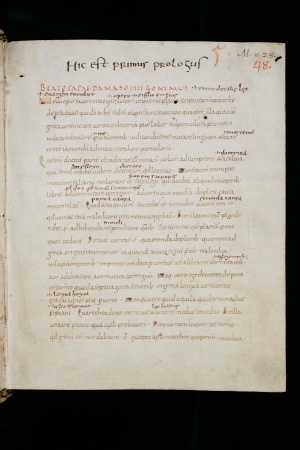

| - | [[image:Codex Sangallensis 48 005.jpg|The epistle of [[Jerome]] to [[Pope Damasus I]]]] | + | [[image:Codex Sangallensis 48 005.jpg|300px|thumb|The epistle of [[Jerome]] to [[Pope Damasus I]]]] |

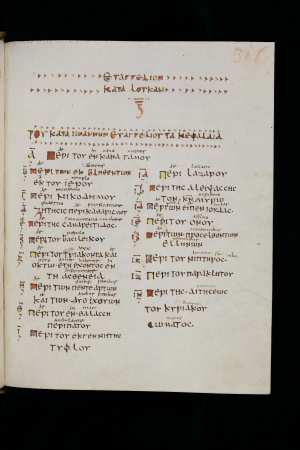

| - | [[image:Codex Sangallensis 48 316.jpg|Tables of κεφαλαια for John]] | + | [[image:Codex Sangallensis 48 316.jpg|300px|thumb|Tables of κεφαλαια for John]] |

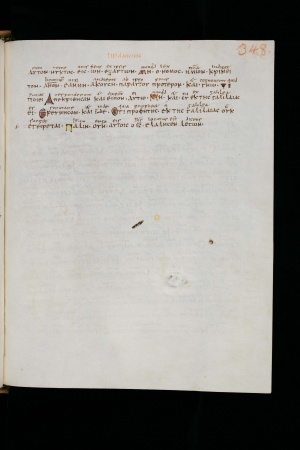

| - | [[image:Codex Sangallensis 48 348.jpg|It lacks John 7:53-8:11]] | + | [[image:Codex Sangallensis 48 348.jpg|300px|thumb|It lacks John 7:53-8:11]] |

== See also == | == See also == | ||

Revision as of 16:36, 11 September 2010

Codex Sangallensis, designated by Δ or 037 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering), ε 76 (von Soden), is a diglot Greek-Latin uncial manuscript of the four Gospels. Usually it is dated palaeographically to the 9th, only according to the opinions of few palaeographers to the 10th century.[] It was named by Scholz in 1830.[]

Contents |

Description

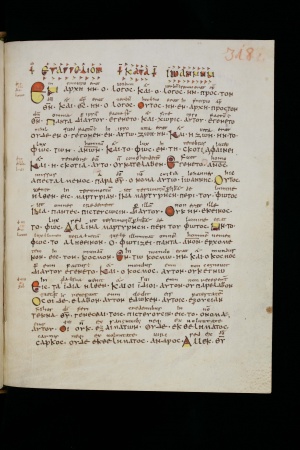

The codex contains 198 parchment leaves (actual size 23 cm by 18.5 cm). The text is written in one column per page, and 17-28 lines per page,[] in large semi-uncial letters.[]

The codex contains almost the complete text of the four Gospels with only one lacunae in John 19:17-35. The Latin text is written above the Greek (as Codex Boernerianus) and in the minuscule letters. It is decorated, but decorations were made by inartistic hand.[] It contains prolegomena, the Epistle of Jerome to Pope Damasus I, the Eusebian Tables, tables of κεφαλαια both in Greek and Latin, τιτλοι, Ammonian Sections, Eusebian Canons in Roman letters.[]sup>[]</sup>

The texts of Mark 7:16 and Mark 11:26 are omitted. The Pericope Adulterae (John 7:53-8:11) is omitted, but blanked space was left (for the pericope).

Text

The Greek text of the Gospel of Mark is a representative of the late Alexandrian text-type (similar to Codex L),[] and in rest of the gospels the Byzantine text-type (as in Codex Athous Lavrensis). Aland placed it in Category III.[]

- Textual variants

- In Matthew 27:35 it has additional phrase τα ιματια μου εαυτοις, και επι τον ιματισμον μου εβαλον κληρον together with codices: Θ, 0250, f1, f13, 537, 1424.

- In Matthew 1:12 it reads Ζορομβαβαβελ for Ζοροβαβελ.[]

- In Mark 4:19 it has unique variant η αγαπη του πλουτου (the love of wealth), other manuscripts have η απατη του πλουτου, απαται του πλουτου or απαται του κοσμου.[]

Latin text

The Latin version seems a mixture of the Vulgate with Old Latin Itala, and altered and accommodated to the Greek as to be of little critical value.

The interlinear Latin text of the codex is remarkable for its alternative readings in almost every verse, e.g. uxorem vel coniugem for την γυναικα in Matthew 1:20.[]

History

The codex was written in the West, possibly in the St. Gallen monastery, by Irish monk in the 9th century.[] It can not be dated earlier, because it has a references to the (heretical) opinions of Godeschalk at Luke 13:24, John 12:40.

It was examined by Gerbert, Scholz, Rettig, J. Rendel Harris. Rettig thought that Codex Sangallensis is a part of the same manuscript as the Codex Boernerianus.

The text of the codex was edited by H. C. M. Rettig in 1836, but with some mistakes (e.g. in Luke 21:32 οφθαλμους instead of αδελφους).[] There are references are made to the opinions of Godeschalk († 866) in Luke 13:24; John 12:40 and to Hand Aragon († 941).[] The Latin text in a major part represents the Vulgata.[]

The codex is located, in the Abbey library of St. Gallen (48) at St. Gallen.[]

Gallery

See also

References

- 1. Kurt Aland, and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1995, p. 118.

- 2. F. H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, (George Bell & Sons: London, 1894), vol. 1, p. 156.

- 3. C. R. Gregory, "Textkritik des Neuen Testaments", Leipzig 1900, vol. 1, p. 86.

- 4. Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, Oxford University Press, New York, Oxford 2005, pp. 82.

- 5. F. H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, (George Bell & Sons: London, 1894), vol. 1, p. 157.

- 6. Editio Octava maiora, p. 3

- 7. NA26, p. 100.

- 8. UBS3, p. 321

- 9. F. H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, (George Bell & Sons: London, 1894), vol. 2, p. 51.

- 10. C. R. Gregory, "Textkritik des Neuen Testaments", Leipzig 1900, vol. 1, p. 87.

Further reading

- H. C. M. Rettig, Antiquissimus quattuor evangeliorum canonicorum Codex Sangallensis Graeco-Latinus intertlinearis, (Zurich, 1836).

- Gustav Scherrer, Verzeichniss der Handschriften der Stiftsbibliothel. von St. Gallen ..., (Halle, 1875).

- J. Rendel Harris, The codex Sangallensis (Δ). A Study in the Text of the Old Latin Gospels, (London, 1891).

External links

- Codex Sangallensis Δ (037): at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism

- Codex Sangallensis 48 images of the codex at the Stiffsbibliothek St. Gallen