Theodore Beza

From Textus Receptus

(→Beza's Greek New Testament) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

===Beza's Greek New Testament=== | ===Beza's Greek New Testament=== | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | In [[1565 AD|1565]] he issued an edition of the [[Greek]] [[New Testament]], accompanied in parallel columns by the text of the [[Vulgate]] and a translation of his own (already published as early as 1556). Annotations were added, also previously published, but now he greatly enriched and enlarged them. | ||

In the preparation of this edition of the Greek text, but much more in the preparation of the second edition which he brought out in 1582, Beza may have availed himself of the help of two very valuable manuscripts. One is known as the ''[[Codex Bezae]]'' or ''Cantabrigensis, '' and was later presented by Beza to the University of Cambridge; the second is the ''[[Codex Claromontanus]]'', which Beza had found in Clermont (now in the National Library at Paris). | In the preparation of this edition of the Greek text, but much more in the preparation of the second edition which he brought out in 1582, Beza may have availed himself of the help of two very valuable manuscripts. One is known as the ''[[Codex Bezae]]'' or ''Cantabrigensis, '' and was later presented by Beza to the University of Cambridge; the second is the ''[[Codex Claromontanus]]'', which Beza had found in Clermont (now in the National Library at Paris). | ||

| - | It was not, however, to these sources that Beza was chiefly indebted, but rather to the previous edition of the eminent [[Robert Estienne]] (1550), itself based in great measure upon one of the later editions of [[Erasmus]]. Beza's labors in this direction were exceedingly helpful to those who came after. The same thing may be asserted with equal truth of his Latin version and of the copious notes with which it was accompanied. The former is said to have been published over a hundred times. | + | It was not, however, to these sources that Beza was chiefly indebted, but rather to the previous edition of the eminent [[Robert Estienne]] ([[1550 AD|1550]]), itself based in great measure upon one of the later editions of [[Erasmus]]. Beza's labors in this direction were exceedingly helpful to those who came after. The same thing may be asserted with equal truth of his Latin version and of the copious notes with which it was accompanied. The former is said to have been published over a hundred times. |

| - | Although some contend that Beza's view of the doctrine of predestination exercised an overly dominant influence upon his interpretation of the Scriptures, there is no question that he added much to a clear understanding of the New Testament. | + | Although some contend that Beza's view of the doctrine of predestination exercised an overly dominant influence upon his interpretation of the Scriptures, there is no question that he added much to a clear understanding of the [[New Testament]]. |

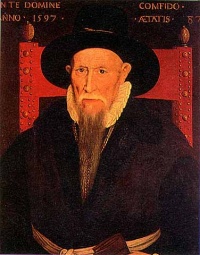

[[image:Beza 1597.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Theodore Beza]] | [[image:Beza 1597.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Theodore Beza]] | ||

| - | |||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Revision as of 21:46, 24 January 2011

Theodore Beza (Théodore de Bèze or de Besze) (June 24, 1519 – October 13, 1605) was a French Protestant Christian theologian and scholar who played an important role in the early Reformation. A member of the monarchomaque movement who opposed absolute monarchy, he was a disciple of John Calvin and lived most of his life in Switzerland.

Beza's Greek New Testament

In 1565 he issued an edition of the Greek New Testament, accompanied in parallel columns by the text of the Vulgate and a translation of his own (already published as early as 1556). Annotations were added, also previously published, but now he greatly enriched and enlarged them.

In the preparation of this edition of the Greek text, but much more in the preparation of the second edition which he brought out in 1582, Beza may have availed himself of the help of two very valuable manuscripts. One is known as the Codex Bezae or Cantabrigensis, and was later presented by Beza to the University of Cambridge; the second is the Codex Claromontanus, which Beza had found in Clermont (now in the National Library at Paris).

It was not, however, to these sources that Beza was chiefly indebted, but rather to the previous edition of the eminent Robert Estienne (1550), itself based in great measure upon one of the later editions of Erasmus. Beza's labors in this direction were exceedingly helpful to those who came after. The same thing may be asserted with equal truth of his Latin version and of the copious notes with which it was accompanied. The former is said to have been published over a hundred times.

Although some contend that Beza's view of the doctrine of predestination exercised an overly dominant influence upon his interpretation of the Scriptures, there is no question that he added much to a clear understanding of the New Testament.