Textual criticism

From Textus Receptus

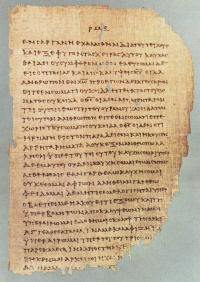

Textual criticism (or lower criticism) is a branch of literary criticism that is concerned with the identification and removal of transcription errors in the texts of manuscripts. Ancient scribes made errors or alterations when copying manuscripts by hand.[1] Given a manuscript copy, several or many copies, but not the original document, the textual critic seeks to reconstruct the original text (the archetype or autograph) as closely as possible. The same processes can be used to attempt to reconstruct intermediate editions, or recensions, of a document's transcription history.[2] The ultimate objective of the textual critic's work is the production of a "critical edition" containing a text most closely approximating the original.

There are three fundamental approaches to textual criticism: eclecticism, stemmatics, and copy-text editing. Techniques from the biological discipline of cladistics are currently also being used to determine the relationships between manuscripts.

The phrase lower criticism is used to describe the contrast between textual criticism and "higher" criticism, which is the endeavor to establish the authorship, date, and place of composition of the original text.

Contents |

History

Textual criticism has been practiced for over two thousand years. Early textual critics were concerned with preserving the works of antiquity, and this continued through the medieval period into early modern times until the invention of the printing press.

Many ancient works, such as the Bible and the Greek tragedies, survive in hundreds of copies, and the relationship of each copy to the original may be unclear. Textual scholars have debated for centuries which sources are most closely derived from the original, hence which readings in those sources are correct. Although biblical books that are letters, like Greek plays, presumably had one original, the question of whether some biblical books, like the gospels, ever had just one original has been discussed.[] Interest in applying textual criticism to the Qur'an has also developed after the discovery of the Sana'a manuscripts in 1972, which possibly date back to the 7-8th century.

In the English language, the works of Shakespeare have been a particularly fertile ground for textual criticism—both because the texts, as transmitted, contain a considerable amount of variation, and because the effort and expense of producing superior editions of his works have always been widely viewed as worthwhile.[] The principles of textual criticism, although originally developed and refined for works of antiquity, the Bible, and Shakespeare,[] have been applied to many works, extending backwards from the present to the earliest known written documents, in Mesopotamia and Egypt—a period of about five millennia.

Basic notions and objectives

The basic problem, as described by Paul Maas, is as follows:

- "We have no autograph manuscripts of the Greek and Roman classical writers and no copies which have been collated with the originals; the manuscripts we possess derive from the originals through an unknown number of intermediate copies, and are consequentially of questionable trustworthiness. The business of textual criticism is to produce a text as close as possible to the original (constitutio textus)." []

Maas comments further that "A dictation revised by the author must be regarded as equivalent to an autograph manuscript". The lack of autograph manuscripts applies to many cultures other than Greek and Roman. In such a situation, a key objective becomes the identification of the first exemplar before any split in the tradition. That exemplar is known as the archetype. "If we succeed in establishing the text of [the archetype], the constitutio (reconstruction of the original) is considerably advanced.[]

The textual critic's ultimate objective is the production of a "critical edition". This contains a text most closely approximating the original, which is accompanied by an apparatus criticus (or critical apparatus) that presents:

- the evidence that the editor considered (names of manuscripts, or abbreviations called sigla),

- the editor's analysis of that evidence (sometimes a simple likelihood rating), and

- a record of rejected variants (often in order of preference).[]

Process

Before mechanical printing, literature was copied by hand, and many variations were introduced by copyists. The age of printing made the scribal profession effectively redundant. Printed editions, while less susceptible to the proliferation of variations likely to arise during manual transmission, are nonetheless not immune to introducing variations from an author's autograph. Instead of a scribe miscopying his source, a compositor or a printing shop may read or typeset a work in a way that differs from the autograph.[] Since each scribe or printer commits different errors, reconstruction of the lost original is often aided by a selection of readings taken from many sources. An edited text that draws from multiple sources is said to be eclectic. In contrast to this approach, some textual critics prefer to identify the single best surviving text, and not to combine readings from multiple sources.[]

When comparing different documents, or "witnesses", of a single, original text, the observed differences are called variant readings, or simply variants or readings. It is not always apparent which single variant represents the author's original work. The process of textual criticism seeks to explain how each variant may have entered the text, either by accident (duplication or omission) or intention (harmonization or censorship), as scribes or supervisors transmitted the original author's text by copying it. The textual critic's task, therefore, is to sort through the variants, eliminating those most likely to be un-original, hence establishing a "critical text", or critical edition, that is intended to best approximate the original. At the same time, the critical text should document variant readings, so the relation of extant witnesses to the reconstructed original is apparent to a reader of the critical edition. In establishing the critical text, the textual critic considers both "external" evidence (the age, provenance, and affiliation of each witness) and "internal" or "physical" considerations (what the author and scribes, or printers, were likely to have done).[]

The collation of all known variants of a text is referred to as a variorum, namely a work of textual criticism whereby all variations and emendations are set side by side so that a reader can track how textual decisions have been made in the preparation of a text for publication.[] The Bible and the works of William Shakespeare have often been the subjects of variorum editions, although the same techniques have been applied with less frequency to many other works, such as Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass,[] and the prose writings of Edward Fitzgerald.[]

Eclecticism

Eclecticism refers to the practice of consulting a wide diversity of witnesses to a particular original. The practice is based on the principle that the more independent transmission histories are, the less likely they will be to reproduce the same errors. What one omits, the others may retain; what one adds, the others are unlikely to add. Eclecticism allows inferences to be drawn regarding the original text, based on the evidence of contrasts between witnesses.

Eclectic readings also normally give an impression of the number of witnesses to each available reading. Although a reading supported by the majority of witnesses is frequently preferred, this does not follow automatically. For example, a second edition of a Shakespeare play may include an addition alluding to an event known to have happened between the two editions. Although nearly all subsequent manuscripts may have included the addition, textual critics may reconstruct the original without the addition.

The result of the process is a text with readings drawn from many witnesses. It is not a copy of any particular manuscript, and may deviate from the majority of existing manuscripts. In a purely eclectic approach, no single witness is theoretically favored. Instead, the critic forms opinions about individual witnesses, relying on both external and internal evidence.[]

Since the mid-19th century, eclecticism, in which there is no a priori bias to a single manuscript, has been the dominant method of editing the critical Greek text of the New Testament (currently, the United Bible Society, 4th ed. and Nestle-Aland, 27th ed.). Even so, the oldest manuscripts, being of the Alexandrian text-type, are the most favored, and the critical text has an Alexandrian disposition.[] While 99% of Greek New Testament manuscripts favor Textus Receptus type readings, most scholars who favor the critical text have rejected those readings in favor of the Alexandrian text-type, primarily two manuscripts, Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus.

External evidence

<--edited to here--> External evidence is evidence of each physical witness, its date, source, and relationship to other known witnesses. Critics will often prefer the readings supported by the oldest witnesses. Since errors tend to accumulate, older manuscripts should have fewer errors. Readings supported by a majority of witnesses are also usually preferred, since these are less likely to reflect accidents or individual biases. For the same reasons, the most geographically diverse witnesses are preferred. Some manuscripts show evidence that particular care was taken in their composition, for example, by including alternative readings in their margins, demonstrating that more than one prior copy (exemplar) was consulted in producing the current one. Other factors being equal, these are the best witnesses.

There are many other more sophisticated considerations. For example, readings that depart from the known practice of a scribe or a given period may be deemed more reliable, since a scribe is unlikely on his own initiative to have departed from the usual practice.[]

See also

Topics

- Authority (textual criticism)

- A Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture

- Biblical glosses

- Categories of New Testament manuscripts

- Biblical manuscript

- Bible version debate

- Comma Johanneum

- Hermeneutics

- John 21

- List of omitted Bible verses

- Mark 16

- Palaeography

- Pericope Adulteræ

- Source criticism

- Wiseman hypothesis

- List of Bible verses not included in modern translations

- Modern English Bible translations

- Textus Receptus

- Dean Burgon Society

- Biblical manuscripts

Critical editions

- Hebrew Bible

- Septuaginta - Rahlf's 2nd edition

- Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia - 4th edition

- New Testament

- Editio octava critica maior - Tischendorf edition

- The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text - Hodges & Farstad edition

- The New Testament in the Original Greek - Westcott & Hort edition

- Novum Testamentum Graece Nestle-Aland 27 edition (NA 27)

- United Bible Society's Greek New Testament (UBS4)

- Novum Testamentum Graece et Latine - Merk edition

- Editio Critica Maior - German Bible Society edition

- Critical Translations

- The Comprehensive New Testament - standardardized Nestle-Aland 27 edition[76]

- The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible -- with textual mapping to Masoretic, Dead Sea Scrolls, and Septuagint variants

Lists

- List of New Testament papyri

- List of New Testament uncials

- List of manuscripts

- List of Biblical commentaries

- Textual variants in the New Testament