Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus

From Textus Receptus

for the similarly named manuscript see Codex Petropolitanus (New Testament)

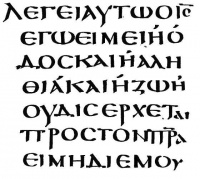

Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus, designed by N or 022 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering), ε 19 (Soden), is a 6th century Greek New Testament codex gospel book. Written in majuscules (capital letters), on 227 parchment leaves, measuring 32 x 27 cm. Paleographically it had been assigned to the 6th century.[]

Contents |

Description

It contains text of the four Gospels with a large number of lacunae.[] The manuscript text is in two columns, 16 lines, 12 letters in line, in large uncial letters. The lettering is in silver ink on vellum dyed purple, with gold ink for nomina sacra (ΙΣ, ΘΣ, ΚΣ, ΥΣ, and ΣΩΤΗΡ). It has errors of itacisms, as the change of ι and ει, αι and ε.[]

Before the Gospels placed teh tables of κεφαλαια. Text is divided according to κεφαλαια. At the top of the pages τίτλοι preserved. The Ammonian sections and the Eusebian Canons are presented in the margin.[] Texts of Luke 22:43-44, and John 7:53–8:11 are omitted.

The text is of the Byzantine text-type in a very early stage, with numerous Allien readings. According to Scrivener "it exhibits strong Alexandrian forms".[]

According to Streeter in some parts it has the Caesarean redings. Aland placed it in Category V,[] and it is certain that it is more Byzantine than anything else.

Lacunae

Matthew 1:1-24, 2:7-20, 3:4-6:24, 7:15-8:1, 8:24-31, 10:28-11:3, 12:40-13:4, 13:33-41, 14:6-22, 15:14-31, 16:7-18:5, 18:26-19:6, 19:13-20:6, 21:19-26:57, 26:65-27:26, 26:34-end;

Mark 1:1-5:20. 7:4-20, 8:32-9:1, 10:43-11:7, 12:19-24:25, 15:23-33, 15:42-16:20;

Luke 1:1-2:23, 4:3-19, 4:26-35, 4:42-5:12, 5:33-9:7, 9:21-28, 9:36-58, 10:4-12, 10:35-11:14, 11:23-12:12, 12:21-29, 18:32-19:17, 20:30-21:22, 22:49-57, 23:41-24:13, 24:21-39, 24:49-end;

John 1:1-21, 1:39-2:6, 3:30-4:5, 5:3-10, 5:19-26, 6:49-57, 9:33-14:2, 14:11-15:14, 15:22-16:15, 20:23-25, 20:28-30, 21:20-end.

History

It is understood that the manuscript originated in the imperial scriptorium of Constantinople and was dismembered by crusaders in the 12th century. In 1896 Nicholas II of Russia commissioned Fyodor Uspensky's Russian Archaeological Institute to buy the greater part of it for the Imperial Public Library in St. Petersburg.[].[] The codex was examined by Lambeck, Montfaucon, Treschow, Alter, Hartel, Wickholf, Bianchini, Duchesne.

Wettstein in 1715 examined 4 leaves housed at London (Cotton Titus C. XV). Wettstein cited only 5 of its readings. According to Scrivener it has 57 various readings.[].[]

Treschow in 1773 and Alter in 1787 had given imperfect collations of Vienna fragments.[] Lambeck gave wrong suggestion that Vienna fragments and Vienna Genesis originally belonged to the same codex.[].[]

Tischendorf published fragments of this manuscript in 1846 in his Monumenta sacra et profana. Tischendorf considered it as fragment of the same codex as 6 leaves from Vatican, and 2 leaves from Vienna.[]

The 231 extant folios of the manuscript are kept in different libraries: 182 leaves in Saint Petersburg, Russia, 33 leaves on the Isle of Patmos, Greece, the rest in Rome (6), London (4 folios).[], Vienna (2), New York (1), and Athens (1), and Lerma (1), Greece.

Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus, along with the manuscripts Φ, O, and Σ, belongs to the group of the Purple Uncials.

A facsimile of all fragments was published 2002 in Athens.

See also

References

- 1. Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 1995, Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 113.

- 2. C. R. Gregory, "Textkritik des Neuen Testaments", Leipzig 1900, vol. 1, p. 56-58.

- 3. Scrivener Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, vol. 1. London: George Bell & Sons. p. 141.

- 4. Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration, 1968 etc, Oxford University Press, pp. 54-55.

- 5. Scrivener F. H. A., A Full and Exact Collation of About 20 Greek Manuscripts of the Holy Gospels (Cambridge and London, 1852), p. XL.

- 6. Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, vol. 1. London: George Bell & Sons. p. 139-140.

- 7. F. K. Alter, Novum Testamentum Graecum, ad Codicen Vindobonensem Graece expressum: Varietam Lectionis addidit Franciscus Carolus Alter, 1 vol., Vienna, 999-1001.

- 8. Lambeck, Commentariorum de aug. bibliotheca Caesar. Vinob. ed. alt. opera et studio Adami Franc. Kollarii, Wien, Bd. (Buch) 3 (l776), col. 30-32.

- 9. F. H. A. Scrivener, A Full and Exact Collation of About 20 Greek Manuscripts of the Holy Gospels (Cambridge and London, 1852), p. XL.

- 10. They were named the Codex Cottonianus.

External links

- Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus N (022) at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism

- Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus at the Evangelical Criticism

Further reading

- Constantin von Tischendorf, „Monumenta sacra inedita“ (Leipzig, 1846), pp. 15-24.

- S. P. Tregelles, "An Introduction to the Critical study and Knowledge of the Holy Scriptures", London 1856, pp. 177-178.

- F. H. A. Scrivener, A Full and Exact Collation of About 20 Greek Manuscripts of the Holy Gospels (Cambridge and London, 1852), p. XL. (as j)

- H. S. Cronin, "Codex Purpureus Petropolitanus. The text of Codex N of the gospels edited with an introduction and an appendix", T & S, vol. 5, no. 4 (Cambridge, 1899).

- C. R. Gregory, "Textkritik des Neuen Testaments", Leipzig 1900, vol. 1, pp. 56-59.