Editio Regia

From Textus Receptus

(→See also) |

|||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

| - | + | [[Image:1550 TR.JPG]] | |

* [[Editio Regia Introduction]] | * [[Editio Regia Introduction]] | ||

* [[Complutensian Polyglot Bible]] | * [[Complutensian Polyglot Bible]] | ||

* [[Novum Instrumentum omne]] | * [[Novum Instrumentum omne]] | ||

| - | * [[Textus Receptus]] | + | * [[Textus Receptus]] |

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 09:57, 16 April 2011

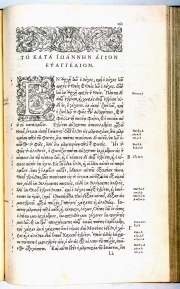

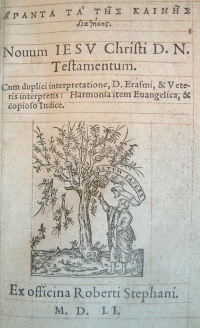

Editio Regia (Royal edition), it is the third and the most important edition of the Greek New Testament of Robert Estienne (1503-1559). It is one of the most important printed editions of the Greek New Testament in history, the Textus Receptus. It was named Editio Regia because of the beautiful and elegant Greek font it uses.

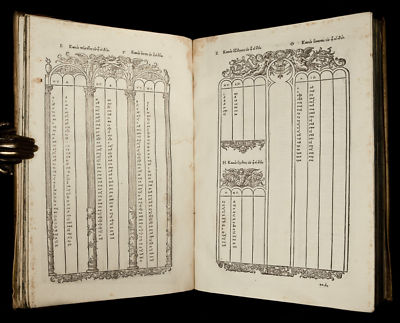

It was edited by Estienne (Stephanus is the Latinized version of the French name Estienne) in 1550 at Paris. It is the first Greek Testament that has a critical apparatus. Estienne entered on the margins of the pages variant readings from 15 Greek manuscripts as well as many readings from the Complutensian Polyglot.[1] He designated all these sources by symbols from α' to ις'. The Complutensian Polyglot was signified by α'. The oldest manuscript used in this edition was the Codex Bezae, which had been collated for him, "by friends in Italy" (secundo exemplar vetustissimum in Italia ab amicis collatum). The majority of these manuscripts are held in National Library of France to the present day.

The text of the editions of 1546 and 1549 was a composition of the Complutesian and Erasmian Novum Testamentum. The third edition approaches more closely to the Erasmian fourth and fifth editions. According to John Mill first and second editions differ in 67 places, and the third in 284 places.[2] The third edition became for many people, especially in England, the normative text of the Greek New Testament. It maintained this position until 1880. The fourth edition used exactly the same text as the third, without a critical apparatus, but the text is divided into numbered verses for the first time in the history of the printed text of Greek New Testament. It was used for the Geneva Bible.

Contents |

Manuscripts and sources used in Editio Regia

In Preface Estienne declared to use sixteen manuscripts.[3]

| Sign | Name | Date | Content | Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α' | Complutensian Polyglot | 16th | New Testament | — |

| β' | Codex Bezae | 5th | Gospels, Acts | University of Cambridge |

| γ' | Minuscule 4 | 13th | Gospels | National Library of France |

| δ' | Minuscule 5 | 13th | New Testament (except Rev) | National Library of France |

| ε' | Minuscule 6 | 13th | New Testament (except Rev) | National Library of France |

| ς' | Minuscule 2817 | 12th | Pauline epistles | University of Basel |

| ζ' | Minuscule 8 | 11th | Gospels | National Library of France |

| η' | Codex Regius | 8th | Gospels | National Library of France |

| θ' | Minuscule 38 | 12th | New Testament (except Rev) | National Library of France |

| ι' | Minuscule 2298 ? | 11th | Acts, Pauline epistles | National Library of France |

| ια' | Unidentified | |||

| ιβ' | Minuscule 9 | 1167 | Gospels | National Library of France |

| ιγ' | Minuscule 393 | University of Cambridge, Kk. 6.4 (?) | ||

| ιδ' | Codex Victorinus, 774 (Minuscule 120) | |||

| ιε' | Minuscule 237 (?) | |||

| ις' | Unidentified | |||

| ? | Minuscule 42 | |||

| ? | Minuscule 111 |

Manuscripts γ', δ', ε', ς', ζ', η', ι', ιε' were taken from the King Henry II's Library (Royal Library of France, now Bibliothèque nationale de France). It was suggested by Wettstein that θ' means Codex Coislinianus (it came to France ca. 1650, and was not available in time of Estienne).

See also

References

- 1. T. H. L. Parker, Calvin's New Testament Commentaries, (London: CSM Press, 1971), p. 103.

- 2. Cited by J. J. Griesbach, Novum Testamentum Graece, vol. 1, Prolegomena, p. XXIII.; F.H. A., Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Cambridge 1861, pp. 387-388.

- 3. F. H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Cambridge 1861, p. 299.